Not my circus, not my monkeys

Learn to stop saving everyone (and why that's the kindest thing you can do)

You’re in a meeting. Someone mentions a problem.

Not your problem.

Not your team.

Not your domain.

But you know how to fix it.

And before you’ve decided anything, you hear yourself say:

“I can take a look.”

Congratulations. You just adopted a circus that was never yours.

For a long time, I thought this was leadership.

I couldn’t walk past a problem without picking it up.

I was the glue.

The fixer.

The one who made things work when they shouldn’t.

It felt responsible.

It felt caring.

It wasn’t.

It was a savior instinct dressed up as competence.

And the part that still surprises me is how long it took me to see the difference —because the system rewards the mistake.

Not every problem needs you

There’s a Polish proverb that captures this boundary:

“Not my circus, not my monkeys.”

It sounds dismissive.

It isn’t.

It’s not about refusing to care. It’s about understanding something most leadership books skip. Energy and attention are finite, and stepping in to save the system can prevent it from fixing itself.

It’s about recognizing a simple truth:

You cannot save everyone.

And trying to will break you and them.

Last week, I wrote about “Who’s got the monkey?”

That post was about delegation.

This one is about boundaries.

“Who’s Got the Monkey?” is what happens when you keep solving your team’s problems.

“Not my circus” is what happens when you keep solving everyone else’s.

One is about giving work back, while the other is about not taking it in the first place.

The core distinction

“Who’s Got the Monkey?” applies when the circus is yours.

You own the team. You own the domain. You are accountable for the outcome.

The problem isn’t commitment.

It’s absorption.

You take execution instead of coaching.

You move faster than your team can learn.

The fix is delegation.

Give the monkey back.

“Not my circus” applies when the circus was never yours.

You don’t own the domain.

You don’t control priorities or budget.

You won’t be accountable when it breaks again.

The problem isn’t delegation.

It’s boundary failure.

You step in because you can.

You stay because no one stops you.

The fix isn’t giving the monkey back.

It’s not taking it at all.

Same instinct, but a different mistake.

One failure mode keeps your team from learning. The other spreads you so thin that no one learns.

Both feel like leadership, but only one is.

The savior complex

If you can solve hard problems, the world will let you. Over time, capable people become the place problems go to die.

People lean on you.

Work flows toward you.

Ambiguity sticks to you.

All because you’re available.

The story sounds noble:

If I can fix it, I should.

What it actually is:

A compulsion to reduce discomfort by taking ownership that isn’t yours.

It feels like responsibility, when it’s often avoidance. Don’t get yourself into a “can-do Groundhog day”.

Two scenarios

Scenario 1: The cross-team infrastructure “assist”

Another team’s CI pipeline is flaky. Deploys fail. People complain.

You’ve seen this before, you know the fix.

You jump in. Add retries. Clean configs. Patch permissions.

The deploy works.

Two weeks later, it breaks again.

Guess who gets pinged?

You didn’t help them build capability.

You became part of their infrastructure.

That’s not collaboration.

That’s silent ownership transfer.

Scenario 2: The temporary fix that becomes permanent

A critical service owned by another team keeps flaking.

Alerts fire at night. Incidents spill into your domain. Your team gets blocked.

You step in “temporarily.”

You add guards, patch a couple of edge cases, maybe even take over deploys for a bit.

Things calm down.

And then something subtle happens.

People stop escalating to the owning team.

They start coming to you.

You didn’t asked to own it… but you already are.

You didn’t mean to take over the service.

You just wanted the noise to stop.

Now you’re maintaining code you don’t control, for a system you didn’t design, with priorities you don’t set.

That’s not leadership. That’s accidental ownership.

And it’s almost impossible to unwind.

What actually broke:

The boundary, not the service.

What it actually costs

Over time, the costs compound.

Ownership becomes unclear.

You become the escalation path by default.

Your own team gets less of you.

Other teams stop developing judgment.

You become a single point of failure.

Great leaders build systems that work without them.

Saviors build systems that collapse when they leave.

The lesson hiding in plain sight

This lesson hides in plain sight. The system rewards the wrong behavior. When you step in, things move faster, people are grateful, and leadership nods.

It feels like progress, but the cost shows up later.

Teams stop developing judgment.

Ownership drifts.

The system quietly reorganizes itself around you.

You’re not fixing problems. You’re postponing the moment the system has to fix itself.

The question should change from “Can I help?” to:

“Is this actually mine?”

When it is right to take a circus

There’s a risk in taking this idea too far.

If no one ever steps in, systems decay. Problems linger, ownership evaporates, and important work stalls because everyone is waiting for someone else to move.

“Not my circus” is not an excuse to disengage.

It’s a filter.

For early leaders, taking on a circus can be exactly the right move.

You’re building judgment and expanding scope. You’re learning how to carry responsibility without dropping it. Saying “I want this circus” can be a conscious, career-shaping decision.

That’s not savior behavior.

That’s growth.

The difference shows up later.

Seasoned leaders already have too many circuses. They don’t lack ownership; they lack capacity.

When they step into every problem, they don’t look committed. They create confusion about who owns what, and they crowd out the next generation of owners who need space to step up.

Caring doesn’t require possession.

You can care deeply about a circus without making it yours. In fact, that’s often the more responsible move.

The goal isn’t fewer circuses, but intentional ownership.

Choose the circuses you’re willing to tend, and support the rest without absorbing them. That’s how systems stay alive, and leaders don’t burn out holding everything together.

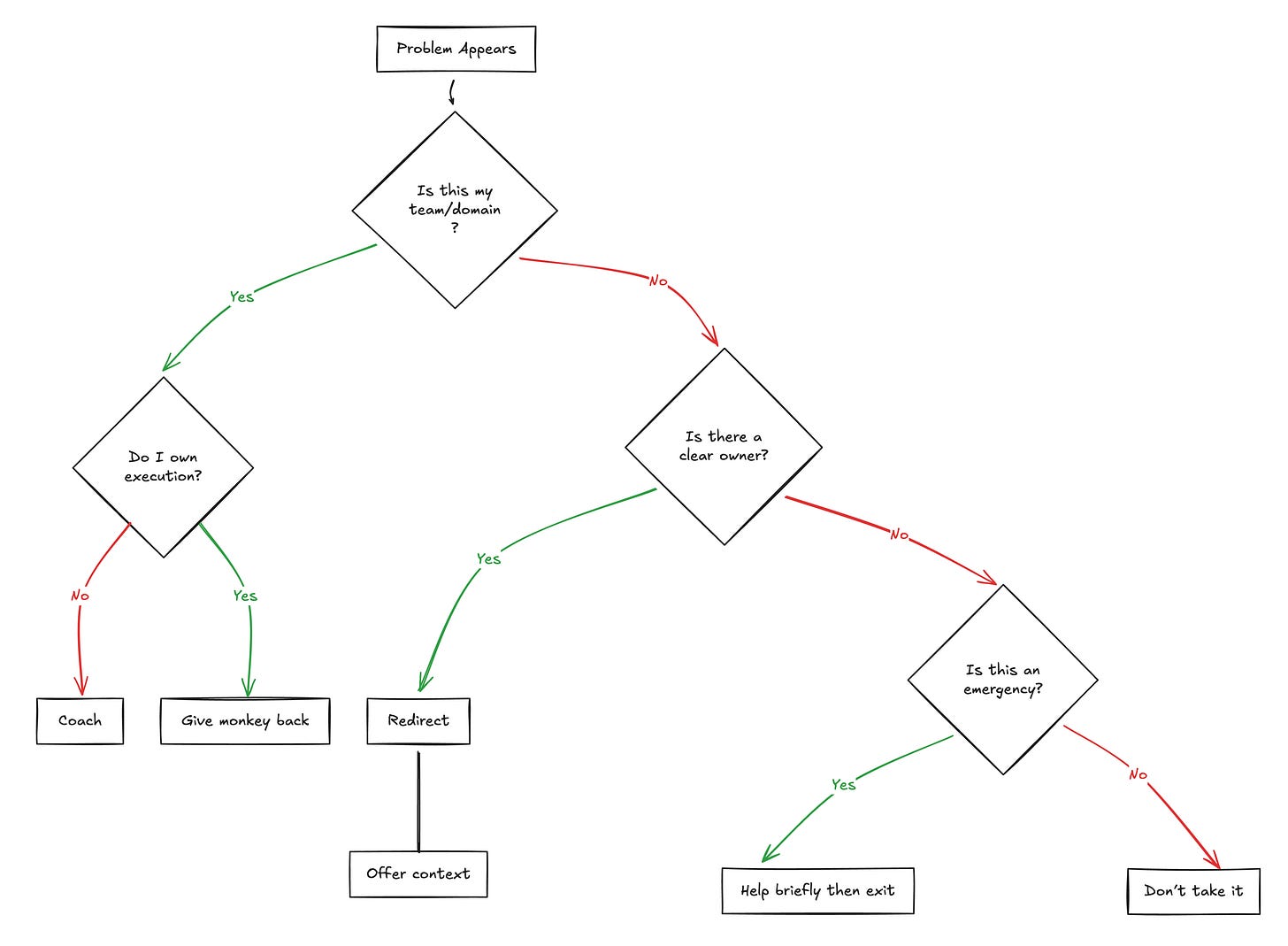

How to decide

If you take it, ask one final question:

What learning or tension am I removing from the system?

If the answer is “the kind it needs,” step back.

Monday morning

Next time a problem shows up, pause.

Before you volunteer.

Before you say, “I’ll handle it.”

Ask:

Is this my circus?

Do I want it to be?

Because “not my circus” is not abdication.

It’s a choice.

If no one ever steps in, systems decay. Ownership evaporates, and work stalls because everyone is waiting for someone else to move.

For early leaders, choosing to take a circus can be exactly right. You’re building judgment, expanding scope, and learning how to carry responsibility without dropping it. Saying “I want this circus” can be a deliberate, career-shaping decision.

That’s not savior behavior.

That’s growth.

The problem shows up later.

Seasoned leaders already have too many circuses. They don’t lack ownership; they lack capacity.

When they step into everything, they don’t look committed. They blur ownership and crowd out the next generation of owners who need space to step up.

Caring doesn’t require possession.

You can care deeply about a circus without making it yours. In fact, that’s often the more responsible move.

So before you step in, ask one more question:

If I take this, what am I preventing the system from learning?

Sometimes the right move is to claim the circus.

Sometimes the right move is to support it without absorbing it.

That judgment is what leadership actually looks like.