Why smart teams make bad decisions together

Understanding the people patterns behind groupthink, incentives, and false alignment

The previous essays covered mental models for everyday thinking: how to think through decisions, understand people, and catch your cognitive biases.

This essay covers team dynamics - how to play the game, work with people, and manage up. The better you get at these three, the less time you spend managing internal team challenges and the more time you can focus on actual business problems.

Here’s what it takes:

self-awareness to observe what’s happening,

pattern recognition to understand the forces at play, and

critical thinking to apply the right response.

No two situations are identical. No two people are the same. Mental models aren’t formulas - they’re lenses that help you see what you’re dealing with.

This essay covers three parts: meetings, 1:1s, and stakeholder communication. What follows are patterns I’ve observed throughout my career - models that helped me understand what’s going on and either prevent preventable problems or mitigate them when they happen.

Unlike code, you can’t just roll back a bad leadership decision with git revert.

But once you see these patterns, you can catch them before they cost you.

Meeting patterns you can’t unsee

You’re in a meeting. Someone proposes a significant change - new product direction, organizational restructure, major technical bet. You go around the room. Everyone nods. Some people add supporting points. Maybe there’s an occasional “easy” question. A mild pushback that gets self-dismissed before it’s fully formed. No major concerns. Everyone’s excited about the new thing - the new frontiers, the fresh start. The old baggage is draining. This new stuff? This is exciting.

You adjourn feeling good. “Great alignment,” you think. Everyone’s on board.

But... Something feels off.

You know this scene. It’s the moment in every horror movie where a group of people is about to enter the dark building. “What could possibly go wrong?” they say.

Everything. Everything could go wrong.

If you see this dynamic, be aware. Not to be a party pooper and rain on everyone’s parade - but in business, someone needs to ask what could go wrong. It’s almost necessary.

The yes-men dynamic is a dangerous one. It’s not happening because people are spineless, but because the system makes agreement safer than truth-telling.

Not many people likes others who ask tough questions. They take energy. They’re “high-maintenance.” Maybe now is a good moment to ask why they’re doing it.

I’ve been that high-maintenance person more times than I can count, especially when seeing groupthink taking over. People nodding, but their micro behaviors telling a different story. Subtle (or not so subtle) dismissal of opposing views. Silence interpreted as agreement. Only considering facts that support the preferred position, ignoring the rest. Explaining the warning signs away.

Not on my watch.

Once you do the intervention to break groupthink a couple of times, people will pick this up and help you stress-test ideas, uncover assumptions and make better decisions. Eventually you’ll have your own mental mugshot book for people you have meetings with regularly so you’ll recognize when they “agree” and when they actually agree. Gently nudge them (call the silence out) when they need it, or, even better, ask each team member on the meeting to explicitly commit or agree to what has been said. Lean back and observe the magic. In healthy orgs people will speak up if they have to commit to something they have second thoughts about.

Let’s unpack what’s actually happening in cases like this. Incentive misalignment is at work, tightly coupled with the yes-men dynamic. People are rewarded for agreeing, not for being right. They get promoted for alignment, not accuracy.

Unfortunately, leadership bears the consequences of bad decisions. Everyone else just wants to keep their jobs, get their bonus, avoid making waves. The incentive structure says: agree, don’t tell hard truths. Agreement wins over truth-telling, unless you help it.

I’m sure you’ve seen this happening before: first person agrees, second person sees that and follows. Third person sees two agreements and assumes they know something. Information cascades are forming before you know it. Suddenly, nobody is thinking independently, everyone is following the crowd. One person’s opinion becomes the team’s consensus without anyone actually validating it. The cascade looks like agreement but it’s just social proof compounding.

Almost all systems reward yes-men and punish truth-tellers. But the best prepared leaders I’ve seen know they need dissenters and respect them - even when it’s not easy to hear. They bring an umbrella to their own parade.

To make this work, you have to intentionally recognize these patterns, point them out, and discuss the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s way cheaper than fixing bad mistakes later.

Now you got your group talking, you dissent - great! I’ve seen a group of leaders discuss the order of columns in a spreadsheet for more than 45 minutes. We spent only 10 minutes deciding whether they should even build all the things in the spreadsheet. I might have even sparked this discussion with a harmless question. This happens to the best of us.

Sometimes you’re involved in this - stop it. Name the waste of time over such trivial decisions, and rather spend time dissenting the big stuff. Bike-shedding is intellectual avoidance wrapped in productive-looking debate, and we’re all guilty of it. Trivial decisions are safe to have opinions about, but they are time wasters.

Next, humor me and do a little math exercise: calculate how much a meeting costs. I do this every time someone’s late, someone goes on a tangent, or we debate things to death without any action. 1 hour with 8 people? You might have burned a person-day. Oops.

Don't decide NOT to have meetings ever again, just being mindful about the cost helps having better, more focused meetings, and make chronically late feel at least a little bad about the pattern.

Redundant thinking is also problematic, it provides no value. I'm sure you've heard this one before:

“If two people in the room always agree, then one of them is one person too many.”

So true. Seek out active disagreement and diverse perspectives to make sure you understand what’s going on. For most meetings you don’t need an audience. Audiences don’t catch your mistakes - they applaud them. What you need are advisors.

It’s all fixable

The easiest way not to get labeled as “difficult person” or “high-maintenance” is to explain others in the meeting that someone should temporarily assume the role of a devil’s advocate and argue against the proposal. Make it their job to find the flaws. Not soft, not too polite, but structured adversarial thinking. Like debate club in school, but for grownups and at work. Rotate the role so everyone gets to be the “bad cop” from time to time.

Most leaders like to talk, like to solve problems, like to have an opinion. But there’s a trap you can fall into when seeking diverse opinions in a group where you don’t peers: you speak first. If you do then everyone might just be responding to or echoing your opinion. Listen first, talk later. The most senior person should practice last to speak. This is extremely true if you’re also a person with a loud voice. More introverted team members might need a bit more time and your silence.

Also, make disagreement mandatory, not optional.

“I need someone to tell me why this is a bad idea” isn’t a rhetorical question. It’s a requirement.

No dissent means the meeting isn’t over. Someone has to argue the other side before you decide. Make dissent obligate, not optional.

The dark side - when leaders actively create yes-men

One of the funniest - but in a dark way - and most frequent patterns you might meet out there is seagull management. You might have done it yourself. I know I did.

You fly in, make noise, crap on everything, fly out. You criticize and comment without sufficient context, offer no solutions, and then leave chaos.

The team is smart. They won’t bring problems to the seagull anymore. They’ll just hide them. And you will all live happily without bad news... for a while, until you meet again, usually when least expected. Don’t be angry with the team then. Rather recognize the seagull management signs before.

And then there are “trust me” decisions, made by authority not merit. Data doesn’t matter. Logic doesn’t matter. The hippo’s gut feeling wins. No, we’re not in the middle of Africa, but in a room with the Highest Paid Person and their Opinion (HiPPO).

When such a person is making all the calls, you can forget about critical thinking. You could hire Braveheart and invite them to your meetings, but it’s better to redesign the system so dissent is expected, safe, and rewarded instead of shushed or fought for with a sword.

Disagreement should have no penalty. Leader speaks last (remember this one?). Criticism is mandatory before big decisions are made.

Enough about meetings. The second biggest thing occupying you is probably people development. I know mine is. And people development is what you notice, not what you schedule. Your 1:1s are more important than you might think.

1:1s aren’t status updates

One of the trickiest 1:1s are the performance reviews. The last conversation you had with them dominates your view of their performance. They had a rough week, missed a deadline, seemed disengaged in yesterday’s meeting. Now you’re sitting in the 1:1 and that’s all you can think about. The three months of solid work before that? Your brain already forgot.

You know making a performance review based on this last conversation is unfair. It’s more common than you’d expect, and no one is immune to it - the recency bias.

Recency bias means recent events carry disproportionate weight. One bad week erases a good quarter. One tense exchange colors the whole relationship. One missed deadline becomes “they’re not reliable.” But you know better.

Keep notes between 1:1s. Track patterns over time, not just last week. “How has this person performed over the last 90 days?” is a better question than “how did they perform yesterday?”

The last conversation wants to rewrite the whole narrative. Notes prevent that.

Also related to performance reviews is how you perceive your team members in general. The best or the worst you can do for someone is to think someone has high potential or write them off as not senior material. This is called Pygmalion effect1.

If you believe someone is high-potential, you give them harder problems, more visibility, better feedback, more of your time. They get more opportunities to grow. They rise to meet your expectations.

If you’ve written someone off as not senior material, you stop giving them challenging work. You don’t invest in their development. You give them the routine stuff. They never get the chance to prove you wrong. They stagnate, confirming your initial belief that they’re not senior material.

Your expectations helped create the outcome you expected.

I’ve seen the effect of doing both. Personally, I lean into “high-potential” until people consistently demonstrate they don’t want me believing in them. It happens, but rarely.

This cuts both ways. Expect greatness, you’ll invest in creating it. Expect mediocrity, you’ll get it.

The question isn’t “Are they high-potential?”

It’s “Am I treating them like they are and did I give them a fair chance?”

You have given them a fair chance, now you observe their behavior.

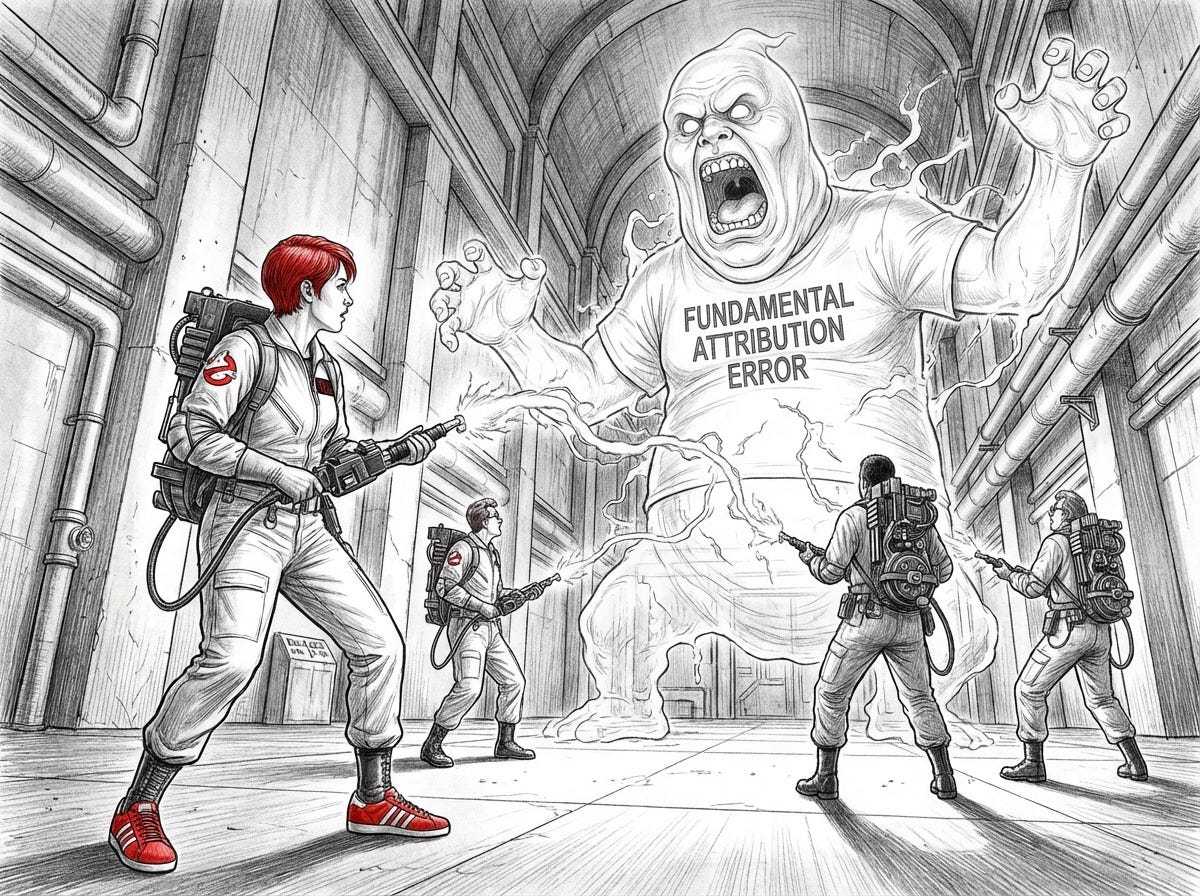

A team member missed the deadline. Your first thought: “They’re not detail-oriented. They don’t take deadlines seriously. They’re not ready for more responsibility.”

When in reality they had one problem after another. The final scope was much greater than the initial one. No one cared (including you) to ask what challenges they faced, and since they’re more introverted, when they tried to explain this, no one listened.

You assumed the person is the problem, not the circumstances - without checking first. The worst scenario is you form a judgement based on this and share it with other leaders.

This is called the fundamental attribution error and needs to be exterminated from leadership like ghost gone bad. I’m thinking about founding a Ghostbusters-like team to make these evil spirits of attribution errors extinct. It’s human, but it should not exist.

Sprinkle your observations with a dose of gray thinking and ask: “What situational factors am I missing? What’s the system doing to them?” The system might be the problem.

Then go fix the system issue. Join Ghostbusters. If it’s not the system, you have material for a difficult conversation. But check first, judge later.

Unmotivated people don’t work at their full potential. Thank you Captain Obvious.

So it’s up to you to help them be motivated.

Here’s a problem: you can’t do it to them or instead of them. Motivation is similar to change - it has to come from within.

You’ve probably noticed this yourself, especially if you ever worked in a startup: people care more when they have skin in the game. Give them ownership. Let them make decisions. Let them see the impact of their work on users.

Nobody washes a rental car.

You might get by with a big motivational speech now and then, but small, visible wins beat this. Remember how good it feels when you look at the progress you made on meaningful work at the end of the day? Your team is no different. This is the progress principle in action. Use it. Celebrate small wins. Replace all-hands pep talks with “We shipped this feature and three customers immediately adopted it” when it happens.

And now one thing we all know but don’t want to admit: you value what you worked hard for. Same goes for your team. They might say differently, but you’ll see it in their eyes and the attitude when they think you’re not watching.

If they poured effort into something, they’ll be invested in making it succeed. And the harder they work, the more they’ll care about the outcome. This is called effort justification. Just make sure they work hard on the right thing at the right time, and you can’t go wrong. Everyone satisfied.

TL;DR: Motivation isn’t about finding the right words. It’s about giving people ownership, showing them progress, and letting them invest effort in something meaningful. But you already know that.

All is going well, your team thrives, but then you notice some of them going astray a bit after having their big win or two. Overconfidence, over-opinionatedness, not listening, too much of “I’ll do it first without thinking, and ask for permission and help with shit shoveling later.” You know you have to do something, but what?

Or you have the other extreme. A team member who is full of ideas, performs extraordinarily, is being proactive - suddenly after a recent project or two becomes quiet, withdrawn. Are they looking for another job? Did you say something wrong? What’s happening?

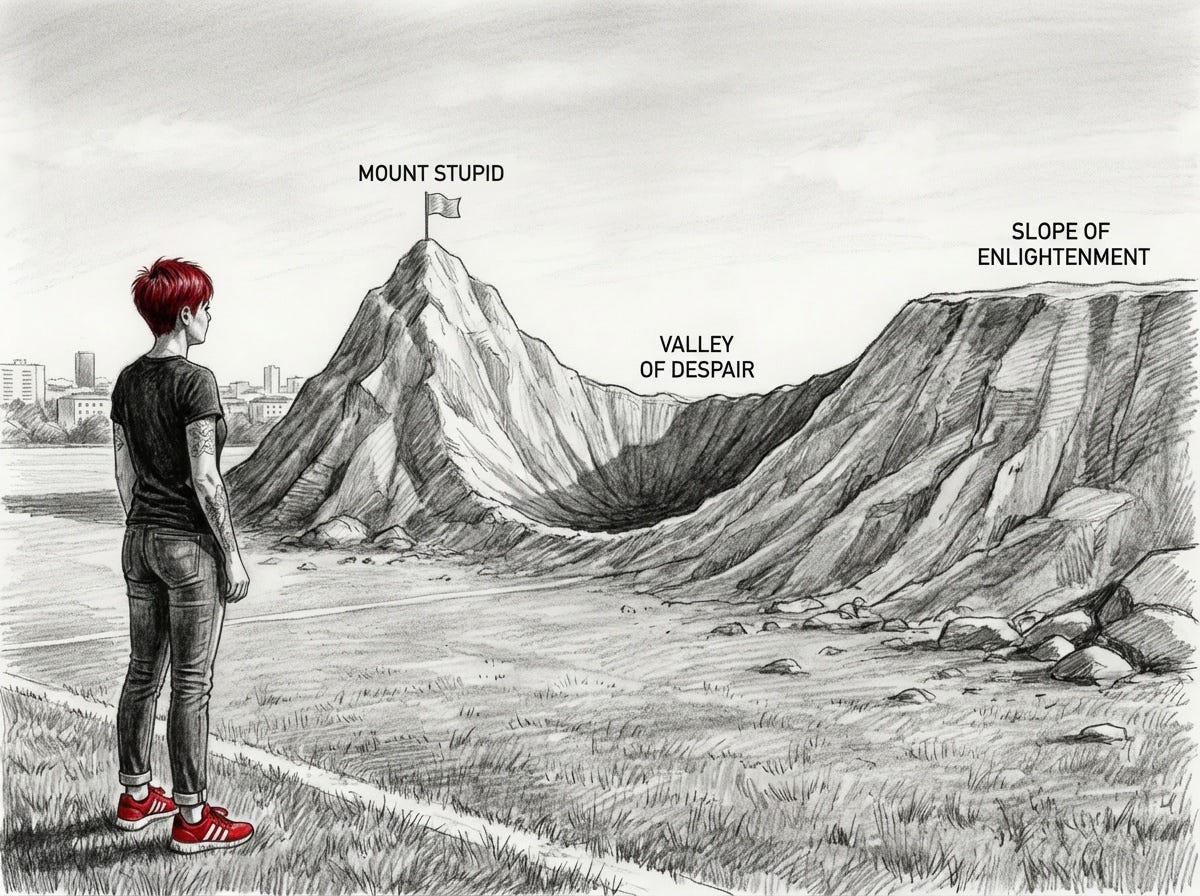

In both cases it’s time to have “the talk.” Not about bees and birds, but about a funny little thing called the Dunning-Kruger effect. Show them the curve:

Mount Stupid: Just learned something, very confident, doesn’t see the complexity.

Valley of Despair: Started working, discovered the complexity, confidence craters.

Slope of Enlightenment: Building competence, understanding the nuance.

Plateau of Sustainability: Actual expertise, accurate self-assessment.

In the first case, you would kindly ask the over-confident person to slowly descend from Mount Stupid, because the longer they stay up there, the worse it gets — although it doesn’t feel this way to them. But it sure does to others. They’re just too polite to say it.

Help the second person come from the Valley of Despair and explain to them it’s normal to get a bit down when you realize how little you know. But that’s okay. You’ll learn, you’ll fail a bit, you’ll win a bit, and eventually you’ll have a healthy relationship with both sides of this.

There’s no shame in climbing to the top of Mount Stupid. We all need to go there to see the view. But it’s a shame to stay there. Also, seeing the Valley is beneficial - a little humbling experience harmed no one. Unless they stayed in the valley.

In both cases it’s you who can lend a hand to help them descend or ascend.

I know the diagram by heart by now, so I can draw it on a whiteboard and explain it to anyone who needs to hear it... or who’s willing to listen. Care to learn about the Dunning-Kruger effect? If you came this far, you already did.

If you use your 1:1s only for status updates, you’re missing out on precious quality time. Personally, I don’t want to miss the opportunity to do something better with it. Like help people develop and get myself out of the job... eventually.

Now that we understand people better, we have to get to another level - to know how to influence people who are not obliged to listen to us, but usually do so. Our other stakeholders.

Stakeholders don’t care about your logic and that’s ok

Let’s say you need buy-in from stakeholders for a major initiative. Resources, timeline, scope - all require approval. You prepare a deck. You present data. You make logical arguments.

And it doesn’t work.

You’re confused. The logic is airtight. The data is clear. The proposal solves a real problem. How did this fail?

I wrote about this before (check “Debating physics in a room full of poets“), but now we’ll take a look from the lens of mental models.

You failed because you think stakeholder communication is information transfer. It isn’t. It’s game theory. It’s about managing incentives, power dynamics, and perception - not just conveying facts.

They will rarely want what you want. Most likely their incentives aren’t aligned with yours. For example, you want to build the right thing long-term. They want to hit quarterly targets. You want sustainable growth. They want to good results in next week’s exec review.

The finance stakeholder cares about budget. The sales stakeholder cares about features that close deals this quarter. The compliance stakeholder cares about security aspects and risk mitigation. None of them care about what you care about. They care about their own goals, measured by their own KPIs. And that's ok, that's normal.

Now that you are aware of the principal-agent problem you’ll understand that assuming alignment is the mistake. Map their incentives instead. Ask yourself: “What does success look like for them? What are they measured on? What keeps them up at night?” Then frame your proposal in terms of their goals, not yours.

Then you might be thinking in years, they’re thinking in quarters... or vice versa, depending if the board meeting is coming up and they need results before it. Sometimes this time horizon mismatch makes alignment nearly impossible, especially when you suggest to address technical debt that won’t show results for six months, but the stakeholder needs a win this quarter. The quarter wins. Every time.

You know this is short-term thinking. They know it too. But the board meeting is in two weeks, and “we’re investing in long-term platform health” doesn’t play as well as “we shipped 3 customer-facing features.” The incentives are honest about what they reward. You have to be honest about the game you’re playing.

When you’re dealing with stakeholders, even your team members, you can’t bypass managing their expectations. And managing expectations is anchoring. When you set an expectation, you’re placing an anchor for how people will judge the outcome.

You set both external and internal expectations.

Tell a customer a feature ships in Q2, and Q2 becomes the anchor. Ship in late Q1, you’re a hero. Ship in early Q3, you’ve failed - even if the feature is excellent. The delivery date matters less than the anchor you set.

Most SaaS leaders try to impress customers with aggressive timelines. “We’ll have that integration done in 2 weeks.” Now you’ve anchored expectations high. Miss by a day and you’ve damaged trust. The aggressive anchor can hurt you.

Your team’s morale and performance is also anchored to the expectations you set. Tell them a feature is “just a quick fix” and they’ll resent if it takes a week. Frame it as “this is complex work” and a week feels reasonable. Same work, different anchor, different morale.

Revenue targets work the same way. Set a stretch goal of $1M when $800K is realistic, and hitting $850K feels like failure. The team did well - they beat realistic projections - but they’re demoralized because they missed the anchor you set. You’ve turned a win into a loss through bad anchoring.

This is where we can screw up quarterly planning. Sometimes we set ambitious targets to “motivate the team,” which just means setting high anchors. We should not be confused when the team is demoralized after a solid quarter that missed the inflated target.

The main lesson: The first estimate anchors expectations. Be smart about it. They don’t say “underpromise and over-deliver” for nothing - it’s a real thing. But beware of extreme sandbagging. Add too much buffer and you’ll lose credibility.

I’m sure you’ll find many more examples in your day-to-day work.

A while back I joked that we could do the anti-pattern of gamification, and build a "wall of shame" feature to encourage more users to one of our tools more and make less mistakes. I swear, I was joking, but what I had in mind is that people feel losses more strongly than equivalent gains. Check the science, it’s there. This is loss aversion.

So keep this in mind when framing your proposals and let them know (your stakeholders) what they’ll lose by not doing it, not just what they’ll gain doing it. “If we don’t invest in this, we’ll lose market share to competitors who are already shipping it” lands harder than “if we do this, we might gain some market share.”

No need to build internal wall of shame, though. Drop it. It’s a terrible idea. And it was a bad joke.

Ready to manage your stakeholders? Not just yet. There is one more thing to keep in mind.

Most of the time you have context they don’t have. They have constraints you don’t see. This gap? The source of misalignment. This is also called information asymmetry.

You know the technical details, the risks, the tradeoffs. They don’t. You’re explaining in technical terms. They’re nodding but not understanding. They know the political dynamics, the budget constraints, the exec priorities. You don’t. You’re wondering why they won’t approve what seems obvious.

Remember the poets mentioned before? Be the physicist who can read and write poems. Bridge the gap. Translate technical to business impact. Ask about their constraints. Make the invisible visible on both sides.

Congrats, you’re all set now… But are you?

I’ve been in stakeholder reviews where everyone nodded enthusiastically. Three hours later, I got five separate 1:1 messages explaining why they actually disagree. Nobody wanted to be the first to object in the room. Everybody wanted to be the one who “raised concerns privately.” The meeting was what... a theater? The real decisions happened in Slack DMs afterward.

What the hell just happened? Preference falsification, that’s what happened. People hide their true preferences to avoid conflict or maintain image. The stakeholder says “sounds good” in the meeting. They don’t mean it. They’re waiting to see what everyone else thinks before committing.

So, if you want to prevent all this, help other leaders to create safe spaces for dissent. Ask directly: “What concerns do you have?” not “Everyone good?”

Probe for real objections before assuming consensus. Get buy-in 1:1 before the group meeting. Pre-wire the decision. Use the group meeting to formalize, not to negotiate.

I do this all the time since I banged my head over this pattern for a while. Now I make sure to understand who are the veto players — people who can kill the proposal. Majority support doesn’t matter if one person can block. If I can’t convince that person with the arguments, there’s little chance I’ll be successful.

To recap: Stakeholder communication isn’t THE ONE presentation. It’s a series of 1:1s building support, pre-wiring decisions, neutralizing objections, creating momentum. By the time you’re in the room presenting, the outcome should already be decided.

Now you ARE ready to kick the proverbial butt. Since you know all the patterns now, I’m confident you won’t kick your own... too often.

You can’t unsee this

Now you’ve seen things that can’t be unseen. Welcome to this side. The view is different here, but very interesting.

I hope I made you at least think about shifting from reacting to patterns to recognizing them, from wondering why logical things don’t work to understanding the forces underneath.

Leadership isn’t about having all the answers. It’s about seeing the patterns that create the problems, then redesigning the systems so the problems stop recurring.

No need to try to be brilliant. Just try to be less wrong, one recognized pattern at a time.

The first time you see one of these patterns, it’s revelatory. The tenth time, it’s useful. The hundredth time, it’s automatic. You stop thinking about the models. You just see the systems.

That’s the goal. Not to memorize frameworks. To rewire how you see leadership so you catch problems before they escalate into something draining you and your team of precious energy and time.

Start with the pattern that’s costing you the most right now.

Part of a series on mental models: how to be less wrong, not be an idiot, lead without breaking your team, and build things without losing your sanity.

The concept is named after the Greek myth of Pygmalion, a sculptor who fell in love with his statue, which then came to life.