Building systems that don’t require heroes

Designing organizations that execute without burnout or fragility

The previous essay was about understanding people: the dynamics in meetings, 1:1s, and stakeholder conversations. This one is about the harder part: building systems that actually work when you’re not there to hold them together.

I’ve learned these lessons the more expensive way, through client projects we never killed but should have, teams that put everything on hold when one person went on vacation (with their laptop), and plans that optimized for everything except what mattered. After reading this, you’ll spot situations that are off much more clearly. You can thank me or curse me later (probably little bit of both), but you can’t say I didn’t warn you.

This essay covers mental models for strategic execution: how to plan, how to measure, and how to build teams that get stronger under stress instead of breaking under pressure.

Planning and measuring what matters

Think beyond step one

It’s quarterly planning time. Everyone has ideas. The backlog is full. Everything seems important. You need to decide: what to work on, what to kill, how to measure success.

First step: think things through a bit more, at least several steps more. Remember second-order thinking from Mental models for thinking clearly? At leadership scale, the stakes are higher and the ripple effects reach more people.

You’re hiring three senior engineers to speed up delivery. First-order thinking would be more engineers mean faster shipping. Case closed. But what happens when you start asking “And then what?”

You figure out that onboarding will most likely overwhelm an already stretched team. You can forget about productivity for at least a quarter. Onboarding takes time. Real time. But short-term setback for mid-term or long-term gain.

Next, seniority can be a double-edged sword. Yes, they bring more experience and knowledge. But they bring strong opinions, too. And three seniors on top of any existing ones can create competing architectural approaches.

These things happen, no use pretending they don’t or can’t. Even if we put all this aside, we need to understand that if the real problem is unclear product strategy, more engineers can make things worse. You can’t hire yourself out of strategic confusion. This just makes the problem more expensive.

I participated in this kind of mistake. Twice. Both times we genuinely thought we were being strategic, and somehow made everything worse. But the second time hurt more — at least I (the fan of mental models) should have known better. It can be fixed, but it requires a lot more energy and time than anticipated.

Think two or three moves ahead before committing resources. Most leadership regrets come from first-order decisions that ignored what happens next.

More is not always better. The first engineer you hire creates massive value. The second engineer adds value, but less than the first. The third adds even less. By engineer number ten, you’re getting a fraction of the impact you got from engineer one. This isn’t about the people, it’s about the system. Communication overhead grows. Coordination costs compound. Onboarding burden increases. The marginal value of each additional resource decreases.

I’ve watched teams double in size and ship half as much. More people, less output. Diminishing returns in action. The answer isn’t always add more resources. Sometimes it’s work differently with what you have.

Debug the system, not the people

Remember systems thinking from Mental models for thinking clearly? It sees the structure, not just the event. At org scale, you’re not debugging code, you’re debugging human systems. And human systems are messier. You can’t just hire a CSI team to help you find the meeting that caused the problem.

Another example that will most likely be familiar: the team keeps missing deadlines. Your first thoughts: they should work harder... or you need to add more people, maybe someone from another team can lend a hand... or yes, you could extend hours?

Let’s look a this situation through the systems thinking lens: why does the system keep creating this outcome in the first place?

Engineering is blocked by Product. Product is waiting on Design. Design doesn’t have clear requirements because leadership hasn’t aligned on strategy. No amount of work harder fixes a system-level problem. The constraint isn’t effort, it’s the structure. Since it’s most likely a system problem, you start optimizing processes down to instructions on the task. You’re at the Final final version 1 of the process document, Product writes more specs. Design creates more mocks. You optimized everything except the real bottleneck and got zero improvement. If leadership alignment is the bottleneck, none of that matters. Work piles up at the constraint. Let me introduce you to theory of constraints that says the system is only as strong as its weakest link. Find this weak link and address it.

Of course it’s not always leadership. I’ve seen teams add engineers when the real constraint was deployment pipeline. Add product managers when the constraint was unclear strategy. Add designers when the constraint was indecisive leadership. They optimized everything except the actual bottleneck.

Find the constraint. Fix it. Then find the next one.

The system moves at the speed of its slowest part.

Feedback loops are important parts of systems. When analyzing challenges, ask yourself “What feedback loops exist?” Because believe it or not, what you reward is what you get more of.

Let’s say you praise someone for working late to hit a deadline. Awesome, you recognized this contribution. What could possibly be wrong with this? A lot of things. First of all, what they learn is that working late gets recognition. Others see this and start working late. Then you as a leader can’t be the first person going home, right? Being part of the team and all? And then working late becomes the culture. People burn out. You meant to recognize dedication. The feedback loop reinforced overwork. How did this escalate?! With you. With good intentions.

I have a small confession to make: my path to hell is probably already paved half-way there with (my) good intentions.

The event is someone working late. The system is what created the incentive to work late. Fix the structure that’s creating the behavior.

If you ever worked at a company older than a year or where the original crew is not present anymore, you’ve seen this: a fence across a road. It seems pointless. You want to remove it. Be it code, process, part of the system, doesn’t matter. Before you tear it down in a fit of let’s bring in a wind of change, ol’ chap Chesterton would like a word with you about Chesterton’s Fence — the idea that warns against removing things you don’t understand. Maybe it’s preventing something you’ve never seen.

That annoying legacy process might exist for a non-obvious reason. The manual approval step that seems like bureaucracy? It might be preventing a compliance issue you’ve never encountered. The code review checklist that feels tedious? It might be catching the bugs that used to ship weekly.

Guilty as charged, I brought down a couple of fences myself, usually trying to prove myself in a new job. But guess what, every time, I learned why the fence was there — usually by experiencing the problem it was preventing.

Now I ask “why does this exist?” before I remove it. Sometimes the answer is “no good reason” and you remove it. Often the answer is “oh, that’s why” and you leave it alone… or create a plan to replace it with something else. Sometime. That plan is now in the backlog at priority 47.

When to kill projects (even the ones YOU started)

You asked why the fence existed, understood the reasoning, and decided to remove it anyway. Now you’re three months into a rewrite that isn’t working. Everyone knows it. But the team keeps going. Why?

Because the hardest part of planning isn’t starting projects. It’s stopping them. Because admitting the project was a mistake feels worse than continuing to be wrong. Because in the moment, it feels like commitment, perseverance, not giving up. The project becomes about proving you weren’t wrong to start it, not about whether it’s the right thing to finish. This is the text-book example of sunk cost fallacy at work.

I remember the meeting like it was yesterday when I finally decided to kill a project we spent more than half a year on. Ouch. I felt like I was admitting failure in front of the entire team.

No one asked “so all that work was for nothing?”, but I could see it in their eyes. It was brutal. I told them that all the work was not for nothing, we still learned a lot, and it takes guts to sunset something like this. It grows on you. But it can also become Voldemort, the one project that should not be named, or an endless pit. We don’t like either. Turns out those are your only two options for a “we-should-totally-kill-this-project” projects you can’t kill.

The six months were gone whether we continued or not. And throwing more good months after bad ones doesn’t make the bad ones come back. It only makes the mistake drag longer. If you wouldn’t choose this project starting from zero today, stop now. It won’t get easier later.

There’s another thing this project taught me. I’m sure you’ve heard about Pareto principle before. Well, I’ve seen it in action. Getting the last 10% of the MVP took more time than getting to the first 90%.

On the other hand, if you use this to your advantage, you can get more of outcomes from less effort. Most of what gets planned won’t move the needle. The team wants to ship 15 features this quarter. Users will love 2, tolerate 3, ignore 10. If you spend equal effort on all 15, you’ve wasted 80% of your capacity. If you identify the 2 that matter and focus there, you deliver more value in less time. The hard part: saying no to 13 things.

To do or not do, this is now the question

Opportunity cost is mentioned a lot at meetings where engineers need to negotiate for time to rewrite part of codebase for easier maintenance vs ship value to the customer instead. If your teams always ship only value to the customers and don’t get enough time to keeping the lights on, the lights might start flickering. So, while the opportunity cost is very important to consider, you should not forget that you also have to maintain what you build.

Let’s say you decided to pursue this huge opportunity and you want to do this big strategic bet. Everyone’s confident. But six months from now, it’s obviously flawed. What did you miss?

It’s quite possible no one remembered to validate enough. If nothing else, you should at least pick a red-team, a group of people to systematically attack your plan before you commit. Not a rubber-stamp review. Structured adversarial thinking. Find every way this could fail. Every assumption that might be wrong. Every risk you didn’t consider.

Or organize a pre-mortem. Imagine it’s six months from now and the strategy failed completely. What happened? Work backwards from that failure. You’ll see risks you missed in the optimistic planning phase.

The fastest way to validate (at least initially) is to give someone explicit permission to tear it apart. If they can’t find any problems, they’re not really trying. Or they’re being polite. Both are useless here. The best red-team findings feel uncomfortable. That’s the point.

Now you came to a point when you have to decide. But not all decisions are made equal.

Some are hard or impossible to reverse, like committing to a platform, hiring an executive, changing a tech stack, or pivoting. These deserve careful thought, red-teaming, hard debates. Then there are decisions that can be easily reversed if you don’t find them working. You try out a new process or change meeting format or experiment with a feature. These kind of things can be done fast, if they don’t work, revert them.

Most decisions are reversible, but sometimes we treat them like they are not and this kills velocity. I’m proud to say we learned this and my team has no issues piloting a new process or new meeting structure. The bit on the reversibility is key to decide how to decide.

Measure what matters without gaming the system

You made the decision, hopefully the right one. How will you know? By measuring progress, of course. Now comes the tricky part.

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Meet Goodhart’s Law. What you measure becomes what people optimize for. Measure the wrong thing, you’ll get exactly what you measured and none of what you wanted.

If you measure number of commits, team starts to commit every line. Deploy frequency? Easy, break every small change into separate deploys. You’ll end up measuring lots of deploys but you won’t ship value faster. The metric became the target, so it stopped measuring what you cared about.

People are remarkably creative when you give them the wrong incentive. Less so when you give them the right one.

Good metrics resist gaming and stay aligned with actual goals. You could use speed + accuracy + user satisfaction instead, or code reviews completed (not just features shipped). No single metric is sufficient. Any metric used alone will be gamed.

The solution is multiple metrics that create tension with each other, forcing tradeoffs that mirror real goals. But this is for another post.

But, let’s assume we haven’t started yet and we need to estimate how long a project will take first. You estimate a project will take 4 weeks. You tell stakeholders 4 weeks. It takes 6 weeks. You’ve damaged trust. You missed the deadline. The team is stressed. Estimation is hard, but the problem is you didn’t build in a margin of safety. The estimate was your best case, not your realistic case.

Margin of safety is the buffer between what you think will happen and what you promise. It’s the difference between “this will probably take 4 weeks” and “I’ll have this to you in 6 weeks.” It’s acknowledging uncertainty and building slack into the system.

But this is the part where AI makes all this interesting.

Traditional margin of safety: “Development takes 2 days, add 1 day buffer = 3 days.”

AI version should be: “AI generates in 2 hours, add 2 days for verification, integration, and fixing = 2+ days.”

But it feels backwards to add more buffer when AI makes it faster. AI makes you feel like you can reduce margins because if it’s wrong, AI can fix it fast. This could be a slippery slope if you don’t understand what AI produced. Eventually it might take even longer if you don’t take the time to evaluate and understand each thing you add to the system. Remember, some mistakes aren’t reversible, like shipping security vulnerability, wrong database schema, or bad architecture (fast implemented, could take months to unwind), so it pays off to be extra careful with them.

I used to think margin of safety was sandbagging. It felt like admitting I wasn’t confident. Now I know it’s the opposite — it’s acknowledging reality. Things go wrong. Dependencies slip. People get sick. Requirements change. The margin of safety absorbs the variance. But with AI this got to a new level.

However, this still holds: ship in 5 weeks instead of 6? You’re a hero. Ship in 7 weeks after promising 4? You’ve failed even if the work is excellent.

Stop bad projects before they consume capacity. Validate good ones before committing. Measure what matters without creating perverse incentives. Think two moves ahead. Look at the whole system, not just the individual parts.

Change the question from “what should we build?” to “what should we stop building so we can focus on what actually matters?”

Managing teams

Apart from what you build, it’s also important how you organize your teams around the work. In my experience people who work together should sit together, it makes things much easier, information flows, there’s less friction.

However, there’s even a larger thing at play, called Conway’s Law. Separate independent teams, not talking to each other? Separate backlogs, priorities and standups. Your system most likely mirrors this. Separate pieces with seams everywhere. If you want to build integrated system, put the people who need to integrate in the same team, with the same goals, talking to each other daily. Just to lean one way or another to talk to someone on the other side of the computer screen. You’ll see the difference.

Now we’re in production and there’s a production issue. Everyone sees it. Nobody fixes it. Why? When everyone assumes someone else will handle it, nobody handles it. And the more people who could fix it, the less likely anyone will.

Responsibility diffuses across the group.

I’m sure you’ve seen this one play. The bug sits in the backlog for months. Someone should fix that. Everyone agrees. Nobody does. Does this mean your team is lazy? No. It means your team is human. Which is somehow worse for getting bugs fixed. This is just bystander effect... in effect. If you notice it, you can fix it simply by making it one person’s explicit responsibility. Once responsibility is assigned, it gets done. When it’s someone should, it never happens.

Have you heard about technical debt? How about cultural one? The shortcuts you take in culture compound over time. Just like technical debt, it’s easier to ignore in the short term. Just like technical debt, it destroys you in the long term. This is cultural debt.

You hire a brilliant engineer, because... they’re brilliant, but unfortunately not in the emotional intelligence and humility department. You let toxic behavior slide because they’re too valuable to lose. The behavior spreads. Other people notice that being difficult gets rewarded. The culture shifts. You avoided one hard conversation. You created a cultural problem that’s harder to fix.

Or you ignore someone’s pattern of avoiding responsibility for skipping testing and just pushing to production... with bugs causing incidents. Multiple. One after another.

Or my favorite: talking about work-life balance and then sending out Slack messages at midnight. Although you might not expect anyone to respond, they will. They did. So I stopped. And apologized. Now, when the need to write something (because I finally got focused time to answer all the pings) is too strong, I schedule it.

Pay down cultural debt like you pay down technical debt. Have hard conversations. Maintain the processes that matter. Protect the culture deliberately.

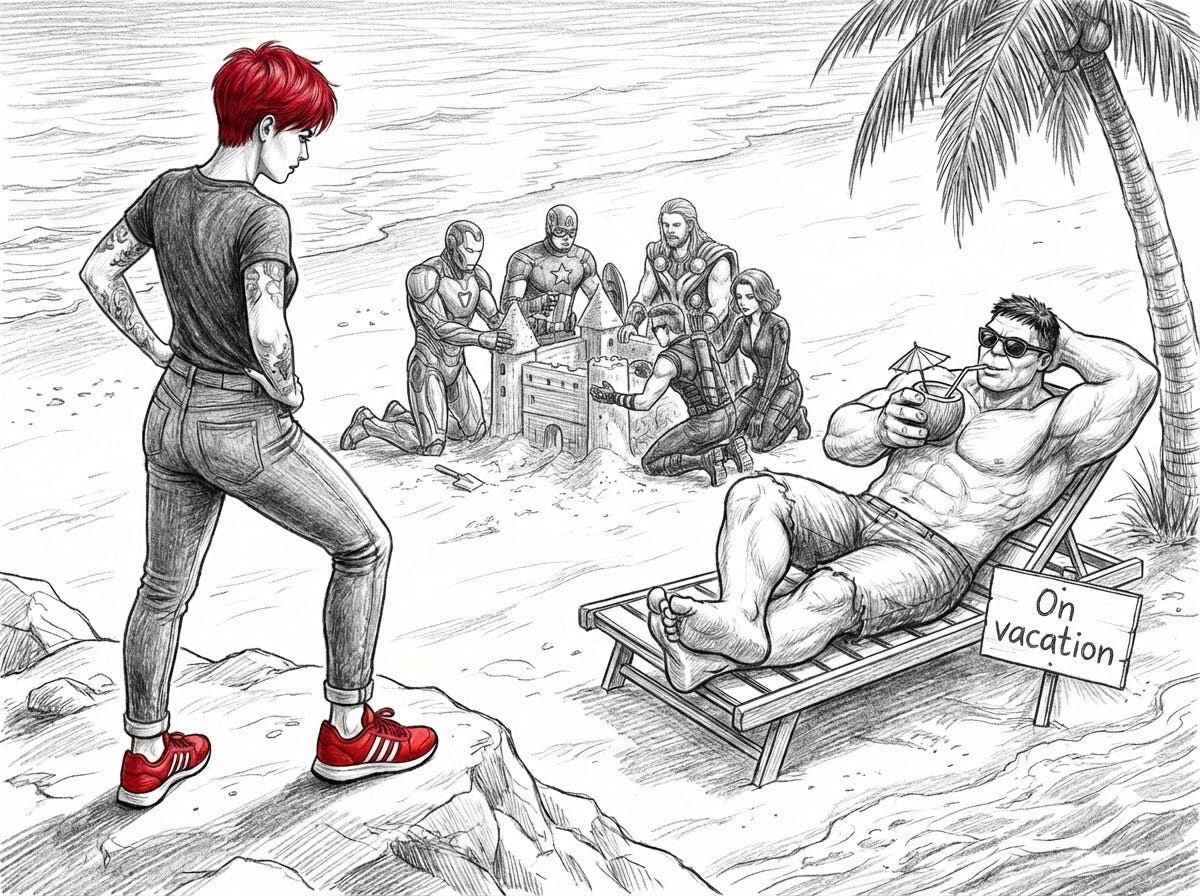

You’ve done a good job as a leader when your best engineer takes vacation without a computer, nothing breaks, projects don’t stall and you figure out you have a high-performing team, and NOT one depending on heroes. It takes work to get here, but it’s worth it. Anything else is a fragile system disguised as one high performer.

I’ve seen both movies play out. In the first one, a hero movie, work is put to a stop when one person is out. All the knowledge is in one person’s head. Only they know how the critical system works. They’re the hero. You’re dependent. And that’s not fair to them or the team.

But I’ve also seen how fragile can turn into antifragile team when leaders and the team put their minds to it and work systematically towards getting stronger under stress. In the second movie, when someone is out, others step up. Knowledge is distributed. Processes don’t require heroes. Documentation exists. No single point of failure.

You can build antifragile systems by thinking a couple of steps ahead and adding some redundancy for critical parts. Rotate people through different areas so at least two people can handle every critical function. Document decisions and context, so people understand the thinking behind, and are not just left to a mysterious comment in code.

If you’re lucky as I am, people like knowledge sharing over knowledge hoarding, they just might need help and tactics how to share it. Give them permission to do it their way, no need to do it super formally. Mentoring works wonders, so does working together and discussing decisions or challenging them.

Although we all like hero movies, they belong at the cinema, not at workplace.

Speaking of handing off work aka delegating, especially projects, is not a walk in a park. Nor is it only handing off work. Because you’ve been thinking about this problem for weeks. You have context, constraints, history, nuances. When you explain it to someone, you assume they know what you know. You skip the context because it’s obvious to you. This is the curse of knowledge. Unless you’re dealing with people who can see in your head (I haven’t yet), it’s not obvious to them. They’re missing 90% of what’s in your head. They build the wrong thing because you didn’t explain the right thing.

I’ve done this more times than I want to admit. The conversation goes like this: I spend 15 minutes delegating what I think is a clear task. Two weeks later, they show me what they built. It’s not even close. Like, not in the same timezone as what I had in mind. My first reaction is frustration — how did they miss the point? Then I realize, I never actually explained the point. I explained the task. The failure isn’t their understanding, it’s my explanation.

How to prevent this?

First, don’t assume context.

Explain the background, the constraints, the history, why this matters, what success looks like.

Over-communicate. Then ask them to explain it back to you. If they can’t, you didn’t explain it well enough.

Actually this is my favorite part when I’m validating my understanding: I say to the person I’ll repeat back to them what I’ve heard to check if I understand correctly. This helps me prevent bad things from happening due to preventable misunderstanding.

Every ambiguity you leave creates rework, misalignment, wasted effort. Being clear upfront takes more time. Being unclear later costs more time. So five more minutes are worth it. I’ve seen a lot senior team members do this, especially when time is of the essence. Might look counter-intuitive to others, but it’s crucial not to waste time with rework. Also, sometimes you can’t put everything in a task, and a well pointed question and rephrasing the problem back can provide much needed context way faster.

The systems create the outcomes

Teams succeed because the system is healthy. And healthy systems stay that way when you catch problems early.

Recognize when your org structure is creating silos instead of integration (Conway’s Law). Notice when responsibility diffuses across the group before that bug sits for months (Bystander effect). Spot cultural shortcuts before they compound (Cultural debt). Build knowledge distribution before you’re dependent on one person (Antifragile). Over-communicate context upfront to prevent rework (Curse of knowledge).

The earlier you spot these patterns, the smaller the course correction. Fix it when it’s a small drift, not a major crisis.

Patterns, patterns everywhere

Once you see these patterns, they’re everywhere. You’ll catch yourself about to commit resources without thinking two moves ahead. You’ll spot the system creating the behavior instead of just blaming the people. You’ll feel that stomach-twist when you’re defending a sunk cost because admitting the mistake feels worse than continuing to be wrong.

I know I’m violating loss aversion here — people are more motivated by avoiding losses than gaining wins. I could’ve focused on all the disasters these mental models describe. But that’s not the point. The goal isn’t to scare you into action. It’s to help you recognize patterns early, when they’re just starting to appear, not when they’re already on fire and need fixing. Prevent bad stuff before it compounds. Encourage good stuff before it’s too late.

Planning meetings will feel different, because you’ll start asking different questions. “What should we kill?” hits different than “what should we build?”

You’ll see the 80% waste in real time and feel the weight of saying no to 13 things so you can focus on the 2 that matter. You’ll recognize the opportunity cost of every yes — the value you’re not creating somewhere else.

You’ll move faster on reversible decisions and slower on irreversible ones. You’ll build margin of safety into estimates instead of promising your best case. You’ll ship early instead of missing deadlines.

Team dynamics will reveal their structure. You’ll recognize Conway’s Law playing out in your architecture. You’ll spot the bystander effect before that bug sits in the backlog for six months. You’ll feel and address the accumulation of cultural debt before your best person tells you in an exit interview that they’ve been unhappy for months.

This is hard work. Building systems that don’t need heroes. Teams that get stronger under stress. Organizations that execute when you’re not in the room.

But it’s worth it. Not because you’ll be perfect — you won’t be. But you’ll catch the problems them earlier. Fix them faster. Build something that doesn’t fall apart when you’re not there to hold it together.

Happy pattern spotting.

Part of a series on mental models: how to be less wrong, not be an idiot, lead without breaking your team, and build things without losing your sanity.