Mental models for thinking clearly

In the age of AI answers, critical thinking is your edge

I was building a product strategy for a side project, partly for the project, partly to stretch my AI muscles and see what it could handle.

I fed ChatGPT my strategy and asked if it made sense.

ChatGPT said it was brilliant.

It wasn’t. The strategy was based on assumptions about user behavior that weren’t true, targeting a market that didn’t exist, with a go-to-market plan I hadn’t validated at all.

ChatGPT had no idea. It just confidently told me why my broken strategy was solid.

AI doesn't push back unless you make it your sparring partner in critical thinking. But that requires you to know what to ask it to challenge.

This is where we are now. You can get an answer to any question in thirty seconds: whether it's a good answer, whether you're even asking the right question, whether the assumptions baked into your prompt are fundamentally broken. It doesn’t say “wait, have you thought about this?”

None of that shows up in the response, unless you explicitly prompt for it.

That’s why critical thinking matters more now, not less.

What AI won’t do for you

AI is incredible at pattern matching, synthesis, and generation. It can help you think through problems, identify risks, challenge assumptions - when you give it the right context and explicitly ask it to.

The problem isn’t that AI can’t do these things. It’s that it makes it too easy to skip the hard thinking.

You can get a plausible-sounding answer without doing the work to:

Frame the question properly

Surface your assumptions so they can be challenged

Verify the output against reality

Catch when you’re solving the wrong problem entirely

Notice when your confidence about an estimate means you’re missing complexity

AI will confidently answer the question you asked. It won’t tell you that you asked the wrong question. It won’t push back unless you explicitly prompt it to. It won’t know that the last three times this pattern appeared in your specific context, it failed for reasons you’re about to ignore again.

Critical thinking is the gap between “this sounds good” and “this will actually work.” It’s the difference between building the thing efficiently and building the right thing. It’s what stops you from spending six months on a strategy that seemed brilliant when you asked about it but reality says is broken.

AI can amplify your thinking. It can’t replace the judgment that comes from experience, stakes, and the discipline to question what you’re actually trying to accomplish.

That’s why critical thinking matters more now, not less. The tool gives you answers faster. You still need to know which questions to ask.

And it’s not just about work.

You need critical thinking when:

Reading news and trying to separate signal from noise

Making family decisions about schools, moves, careers

Evaluating advice from experts who might be confidently wrong

Understanding why your team keeps having the same problem

Deciding if this new framework/methodology/tool is actually better or just shinier

I had a moment of panic while preparing this series. Just when I gave myself a pat on the back to finish fourth out of six essays in this series, I read in one of the online articles how AI made mental models obsolete, that the frameworks we’ve relied on for decades don’t apply anymore. I’d just spent hours on these essays about mental models for leaders and ICs. Hours. And now I’d have to throw everything away? Does it even make sense to write anything? It’s over. I’m doomed.

But then I smacked myself. I don’t do panic. I do critical thinking. OK, some things have changed more than others. AI does change the context. But mental models aren’t rules or laws that break when technology shifts. They’re mechanisms that help us think better, be wrong less often, see patterns we’d otherwise miss. Yes, AI is full of biases and we need to spot them. Yes, we need to understand how AI changes the game. But that doesn’t make all the thinking frameworks obsolete. Some of them survived centuries, other decades, they survived technological advances and war. People have changed, but not so much.

Not everything is lost. Everything just got more interesting. AI hasn’t kill mental models, it just gives them an additional perspective to weave in.

Crisis averted, now let’s see the role mental models play in critical thinking.

Mental models: thinking tools, not formulas

Mental models are frameworks for thinking. They help you recognize patterns you’ve seen before, catch mistakes before you make them, and see systems instead of just symptoms.

They’re not formulas. They’re not rules. They’re more like lenses: different ways of looking at the same problem that reveal different aspects of it.

Most people operate at the event level. Something happens, they react. The system keeps creating the same events, they keep reacting the same way, nothing changes.

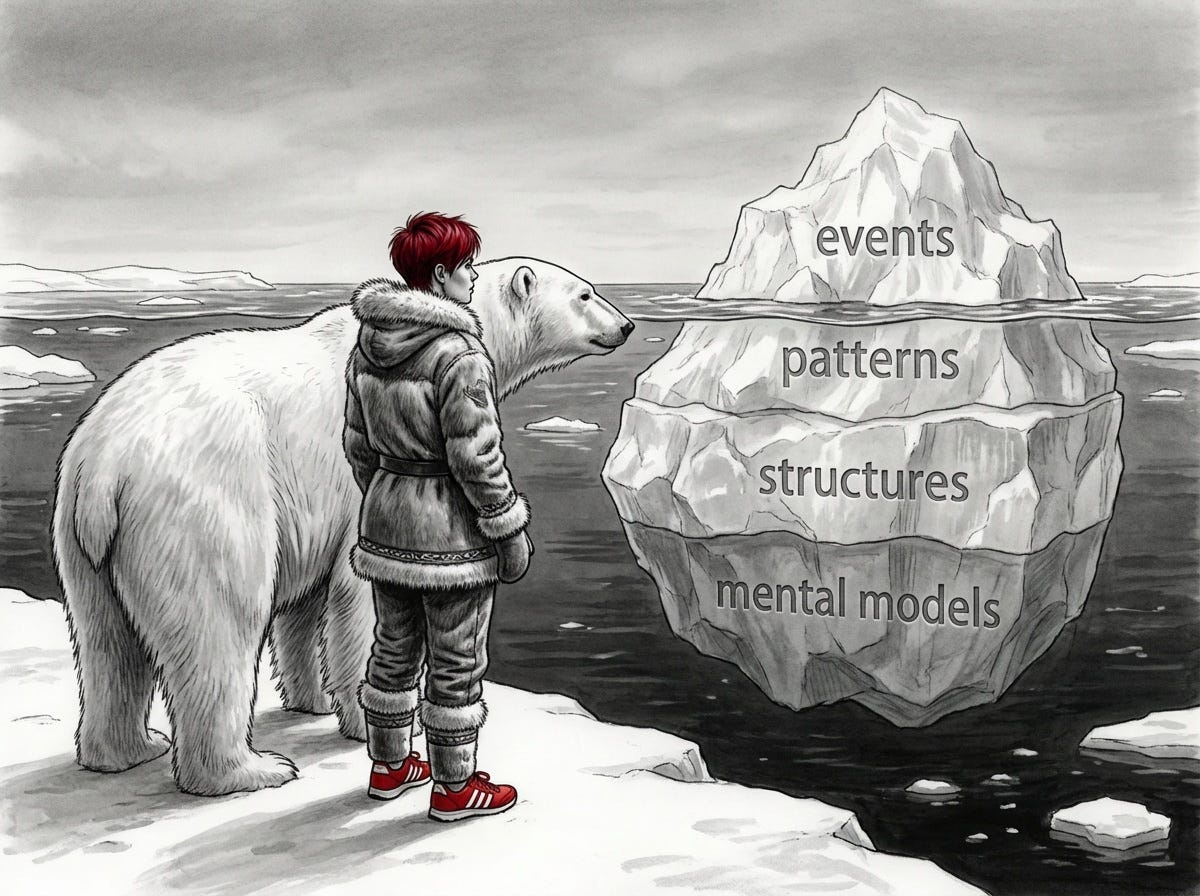

Mental models work at a different level. Think of it like an iceberg.

Events are what you see on the surface. You’re broke at the end of the month. Again.

Patterns are below the surface. This happens every month. That’s a pattern, not a one-time event.

Structures are deeper still. Why does the pattern exist? Impulse purchases. No budget. Lifestyle inflation. The structure creates the pattern which creates the events.

Mental models are at the bottom. The beliefs and assumptions that generate everything above. “I deserve nice things now.” “Budgets are restrictive.” “I’ll make more money later.” These mental models create the structures, which create the patterns, which create the events.

Most people see the event and react. “I’ll be more careful next month. I’ll cut back on coffee.” They’re treating symptoms.

People who use mental models see the iceberg. They question the assumptions creating the structure. “Why do I believe budgets are restrictive? What if tracking spending gives me more freedom, not less?” They fix the root cause. They stop getting the same event on repeat.

That’s what these frameworks do. They help you see past the surface to what’s actually creating the problem.

Some mental models come from specific domains: systems thinking from engineering, opportunity cost from economics, Occam’s Razor from philosophy. But here’s the interesting part: the best ones (the super models) turn out to be useful everywhere. A framework from biology helps you understand organizational dynamics. A concept from physics clarifies a product decision. A tool from psychology explains why your deployment process keeps failing.

The value isn’t in memorizing models. It’s in building a library of thinking tools you can reach for when you’re stuck, when something feels off, when everyone agrees but you’re not sure why.

How this series works

There are hundreds of mental models. Some are more relevant than others. Some apply broadly, others fit specific contexts. They’re guides, not laws. You adapt them, you mix them, you use what works and ignore what doesn’t.

This essay covers how to actually think - mental models for making decisions and understanding people. The frameworks you need whether you’re evaluating a career move, trying to understand why your friend is upset, or figuring out why the “solution” keeps making things worse.

The next essay covers how not to be an idiot - mental models for catching your cognitive biases before they cost you.

After that: models that matter specifically for leaders - when you’re making decisions that affect teams, strategy, and organizations.

And finally: models for engineers - when you’re writing code, making technical decisions, solving engineering problems.

But here’s the key: these aren’t mutually exclusive. The foundational models apply to leadership and engineering. The leadership models work for ICs at tactical scale. The engineering models work for leaders at strategic scale. The difference is the level you’re operating at, not the thinking tool itself.

Leaders apply these at organizational scale. ICs apply them at technical scale. You apply them to life. Same tools, different contexts. I’ll show you the patterns. You do the adaptation.

The models that matter (for everyone)

Making decisions

Think through consequences before you commit

Second-order thinking

Most people think one move ahead. “If I do this, what happens?”

Second-order thinking asks: “And then what? And after that?”

You buy something expensive you can’t really afford. First-order thinking: I want this, I’ll figure out the payments. Second-order thinking: And then what? Monthly payments strain your budget. You start cutting other things. The thing needs maintenance you didn’t budget for. Six months later you’re stressed about money, resenting the purchase, and the initial joy is long gone. The thing you bought to make life better made it worse.

You quit your job without a plan or savings. First-order: I'm finally free from this place. Second-order: And then what? Panic sets in after a month. You take the first job offer out of desperation, which is worse than what you left. Or you burn through savings and now you're anxious about money instead of anxious about work. You traded one stress for a different, often worse, stress.

What if you know about the second-order mental model and think two or three steps ahead before taking the (usually) irreversible decision? You prepare, you plan, you make your exit strategy, you find someone trustful for advice, then when the time is right, you take the job offer you want, not the one you need in desperation.

Now you’re new at the job and you say yes to everything because you want to be helpful. First-order: People like you, you're reliable. Second-order: You're burned out. Quality of your work drops. You start resenting the commitments. People stop trusting you because you're spread too thin. The very thing you did to be helpful makes you unreliable.

However... knowing second-order thinking helps you understand that managing your energy and time is important, your commitments are important, too. You look for advice on how to set healthy boundaries, how to say no and still be helpful, AI can be great sparring partner and can prepare you for this.

You send the angry email. First-order: Feels good, got it off your chest, they needed to hear it. Second-order: Relationship damaged. Trust broken. Now the original problem is worse because you can't have a reasonable conversation anymore. And you can't unsend it. The internet is forever, your regret is also forever, and you get to feel it fresh every time you see them on Zoom, at the cafeteria, in the hallway.

Luckily, this movie unwinds in your head before you hit send. You vent, but you do it in a document you delete afterwards, or email you don't send, and wake up in a morning you don't regret. You still get angry, but you start learning about how to have difficult conversations instead.

You ask ChatGPT about a medical symptom or legal question. First-order: You got an answer, it sounds authoritative, problem solved. Second-order: The answer is confident but wrong. You act on it. The medical advice makes things worse. The legal interpretation costs you money or gets you in trouble. Its confidence lulled you into thinking, you don't need to fact check. You do.

So do it, before you act on it. Instruct AI to cross-reference advice, to suggest what could happen next, what could go wrong. If you lucky, you might have friends who are experts in the field, cross-check with them.

First-order thinking optimizes for immediate outcome. Second-order thinking asks what that outcome creates, and what that creates.

We don’t need to think ten moves ahead. Two or three is enough. We just need to ask: “This works. And then what happens? What does that enable or prevent? What am I not seeing?”

Most regrets come from first-order decisions. We saw the immediate benefit, but missed the downstream cost.

Thinking two or three moves ahead reveals consequences. Most of the time we’re more than capable of doing this. But even when we see potential consequences, we still have to choose. That’s where explicit tradeoffs come in.

Cost-benefit analysis

Every decision has tradeoffs. Cost-benefit analysis makes them explicit instead of letting you pretend they don’t exist. No more putting the head in the sand. Ostriches don’t do it, neither should you.

You want a new car. The benefit is obvious: reliable, safe, looks good, better commute experience. But what’s the actual cost? Not just the sticker price. Higher insurance. Maintenance. Depreciation the moment you drive off the lot. Monthly payments strain your budget. You’re committing to years of car payments. The question isn’t “can I afford this payment?” It’s “is this car worth more to me than everything else I could do with that money over the next five years?”

Most people only see the benefits. They imagine themselves in the new car, not the stress of the payment when an unexpected expense hits. Cost-benefit analysis forces you to look at both sides honestly.

Here’s another tricky one. You’re deciding whether to stay at your current job or leave. Cost of staying: opportunity cost of higher pay elsewhere, frustration with things that won’t change, career stagnation if you’re not growing. Benefit of staying: stability, relationships you’ve built, domain expertise, known problems vs. unknown ones. Cost of leaving: risk of new job not working out, starting over with new people, losing seniority, disruption to life. Benefit of leaving: potentially better pay, growth opportunity, fresh start, escape from current frustrations.

When you write it out, the decision gets clearer. If the main reason to stay is fear of the unknown and the main reason to leave is growth plus money, that’s data. If the reason to stay is you’re genuinely learning and the reason to leave is just more money, different calculus.

Or maybe you decided not to leave and you’re thinking about asking for a promotion. Cost: potential rejection, awkwardness if they say no, increased responsibility and stress if they say yes, relationship strain if you handle it poorly. Benefit: more money, better title, expanded scope, career trajectory. Is the benefit worth the cost? Depends on whether you’re ready for the increased responsibility, whether the timing is right, whether your relationship with your manager can handle the ask. You know the saying “Be careful what you wish for”. I wonder how Eminem and Metallica songs with this lyrics would turn out with cost-benefit model applied.

Here’s one of mine. I was thinking if it’s worth it to purchase a subscription for a specific AI tool. I could keep on using another one that’s free. But... I’ve heard the paid version of this specific tool has much better models and much better results. I could go YOLO and purchase yearly subscription or... I could weigh the costs and benefits of different specific tools out there. What can they do? What can I use them for? Will I use it just for writing, or for programming or something else completely? Is subscription the only cost? Oh, I wasn’t losing sleep over $20 a month, more like 10x this. Worth giving it a thought. If you’re wondering, I did purchase it. I haven’t regretted a single moment.

Cost-benefit analysis doesn’t give you the answer. It makes you honest about what you’re trading.

It’s January. Everyone’s making resolutions. Gym membership, meal prep, moving closer to work. Cost-benefit analysis cuts through the optimism.

Gym membership costs are money, time (including commute to gym), effort, and required consistency. Benefit is fitness and health, but only if you actually go. The January gym is full of people who paid for the benefit without accounting for the cost. Three months later, they’re paying for a membership they don’t use. Honest cost-benefit analysis asks: will I actually go three times a week? If not, the cost is pure waste. February gym is full of empty treadmills and people who learned this lesson. Impulsiveness and gym don’t work well together.

For meal prep at home cost is time (shopping, cooking, cleaning), effort, planning, learning curve if you’re not good at it. Benefit is money saved, healthier eating, control over ingredients. But if meal prep takes three hours every Sunday and you hate every minute, you’ve turned Sunday into a punishment for wanting to eat healthy. Congratulations, you’ve gamified resentment. Is the money saved worth it? Maybe yes if you’re broke and need to save money. Maybe no if your time is better spent elsewhere and you can afford convenience.

Now let’s take a look at moving closer to work. Cost is moving expenses, potentially higher rent, leaving your current neighborhood and the life you’ve built there. Benefit is time saved on commute (maybe an hour a day), less stress, more sleep, better quality of life. Is an extra hour a day worth higher rent? For some people, absolutely. For others, the cost isn’t worth it. There’s no universal answer. Cost-benefit analysis makes your specific tradeoff visible.

When doing this, list the real costs (not just money). List the real benefits (not just the fantasy version). Compare honestly. Then decide if the tradeoff makes sense for you, not for someone else.

Making tradeoffs explicit helps with isolated decisions. But most problems aren’t isolated - they’re part of larger systems.

Systems thinking

Most people see problems as isolated events. Systems thinking sees the structure that keeps creating the problem.

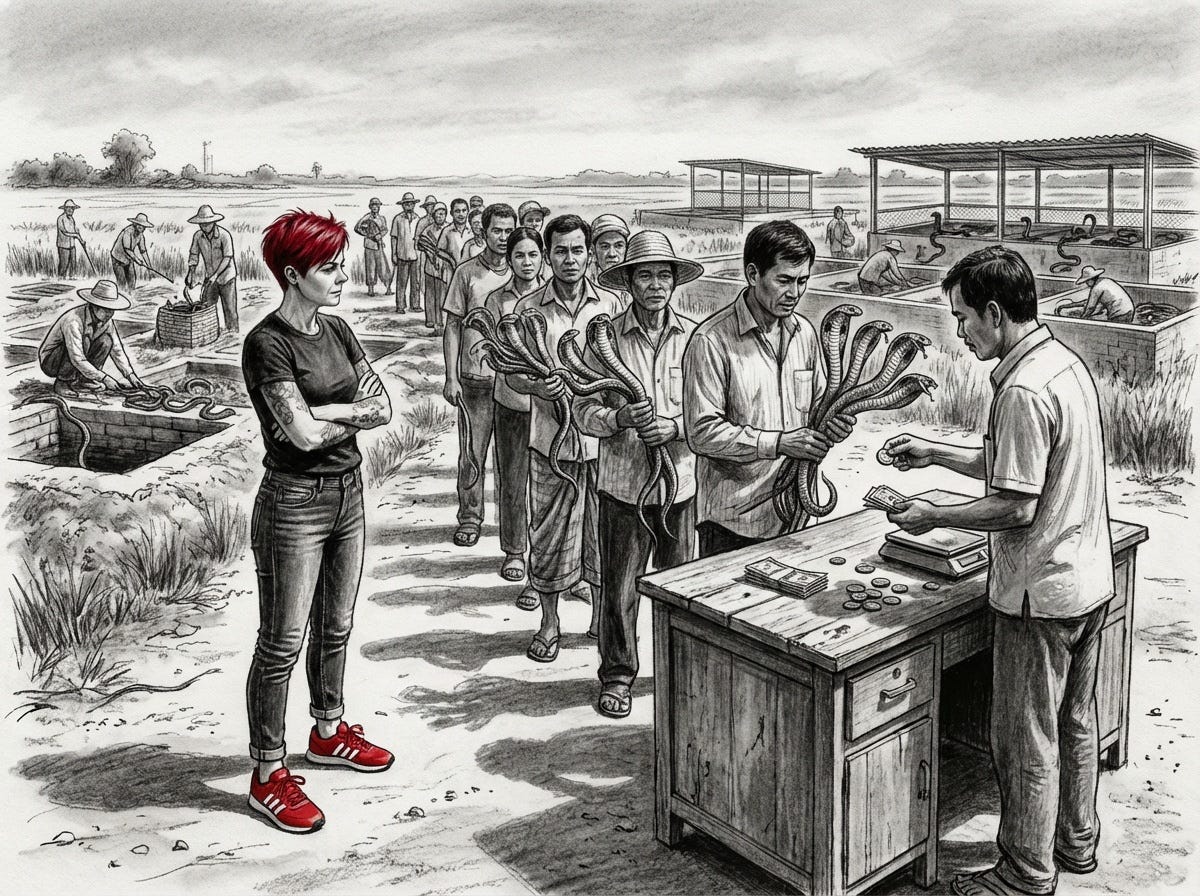

During British colonial rule in Delhi, the government had a cobra problem. Venomous snakes, public safety risk, something had to be done. They offered a bounty for every dead cobra. Seemed logical: create an incentive, reduce cobras, problem solved.

What actually happened: people started breeding cobras to collect the bounty. When the British discovered this and cancelled the program, breeders released their now-worthless snakes. Result: more cobras than before.

This is the cobra effect, now a standard case study in economics and public policy, a well-documented example of so called perverse incentives. A solution that makes the problem worse because it ignores how the system actually works.

Here’s what systems thinking would have caught:

Wrong feedback loop. The British expected a balancing loop: bounty leads to fewer cobras, problem solved. They got a reinforcing loop: more cobras leads to more money, which incentivizes breeding more cobras, which creates even more cobras. The incentive structure rewarded the opposite of what they wanted.

Measuring the proxy, not the goal. They optimized for dead cobras (easy to verify, easy to pay for) instead of reduced cobra population (the actual goal). The metric became the target. When you reward the metric instead of the outcome, people optimize for the metric. This is how you get cobra farms.

Linear thinking in a systemic problem. Their mental model was simple cause and effect: incentive leads to desired behavior leads to problem solved. They ignored how the human economic system would interact with the ecological system. People respond to incentives rationally, but rationally doesn’t always mean the way you want. Systems thinking maps these interconnections before implementing the policy.

Ignoring delays. The unintended consequences weren’t immediate. There was a delay while breeding operations scaled up. By the time the British caught on, the perverse incentive was entrenched and the cobra population had exploded. Systems often have delays between action and consequence. The delay masks the problem until it’s too late.

System boundaries drawn too narrowly. They treated it as a simple “cobra removal” problem. They excluded human economic behavior, market dynamics, and rational self-interest from their analysis. When you draw the system boundary too narrowly, you miss the forces that will undermine your solution.

Systems thinking would have asked: “What behavior does this incentive actually create? What’s the feedback loop? How might people game this? What are the second-order effects? What am I not seeing?” The answer reveals the flaw before you’ve made the problem worse.

Same pattern plays out with AI content recommendations. You use AI to filter news, choose what to read, recommend what to watch. The AI optimizes for engagement—keeping you clicking. Seems helpful. Enter the primary loop. AI shows you content similar to what you engaged with before. You see more of the same perspective. Your view narrows. The algorithm interprets your narrowing as preference and doubles down.

But there are other loops running simultaneously. Content creators see what gets engagement and produce more of it. Now the supply itself is shifting to match your bubble. You’re not just filtering a neutral information stream, you’re reshaping what gets created.

When you share AI-recommended content, your network sees it, engages with similar content, and their algorithms shift. Your bubble and their bubble start reinforcing each other. Social validation makes both of you more confident you’re seeing reality clearly.

Meanwhile, there’s erosion happening to your accumulated exposure to diverse perspectives. This isn’t like weight gain where you notice daily changes. You had a baseline diversity of inputs from before you started using AI filters. That stock is draining and each day you see less variety than you did six months ago. By the time you notice, you’ve lost the reference points to recognize what’s missing.

You realize this and ask AI to challenge you, provide alternative perspectives, find holes in your thinking. AI can do this — if you prompt it with structural constraints. But if you just ask it to challenge me without specifics, you're asking the same optimization engine that created the problem to solve it. What counts as a challenge? The AI shows you disagreements that are intellectually stimulating but not psychologically threatening. You engage with those. The AI learns: "challenging content" means "feels like critical thinking without discomfort." New bubble, same mechanism.

So what actually interrupts the loop? Manual friction. Subscribe to sources you disagree with and force yourself to read them before AI curates anything. Track what percentage of your information comes from outside your engagement history. Set a quota: 20% of reading time goes to randomly selected sources. The system requires structural constraints that prevent optimization, not smarter optimization.

Systems thinking sees the loop before it traps you, but also sees that awareness alone doesn’t break the loop. You need circuit breakers that work even when you’re not paying attention. You might learn something new, open your chakras... or just have a laugh.

Actions ripple. You change one thing, it affects another, which affects another. Cut costs by eliminating training. Short term: budget looks better. Ripple effects: people are less skilled, quality drops, customer complaints increase, you lose clients, revenue drops, now you’re cutting costs again to compensate. You optimized one part of the system and broke three others. The parts are connected. You can’t change one without affecting the rest.

Systems thinking doesn’t mean everything is complicated. It means asking: “What’s the structure creating this outcome? What feedback loops exist? What constraints matter? If I change this, what else changes?” See the system, not just the symptoms. Try to fix the structure, not just the event.

See the system, not just the symptoms. Fix the structure, not just the event.

Understanding people

Stop assuming everyone’s an asshole before checking if they’re just overwhelmed

Hanlon’s razor

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity, ignorance, or misunderstanding.”

Your coworker didn’t respond to your Slack message. You assume they’re ignoring you. They’re not. They’re drowning in pings, fighting three fires, and your message got lost in the noise. You jumped to they don’t respect me when the reality is they’re overwhelmed and didn’t even see it.

Your neighbor’s dog barks every night. You assume they don’t care about disturbing the neighborhood, they’re inconsiderate, they probably hear you complain and ignore it. Reality: they work night shift and aren’t home when it happens. They have no idea the dog is barking. You’ve been building a case against their character based on something they don’t even know is happening.

The cashier was short with you, barely made eye contact, seemed annoyed. You assume they hate their job or they’re just rude. Reality: you’re the 11th customer today, and the first 10 were awful. Someone yelled at them about a price they don’t control. Someone else berated them for being too slow. Someone returned a worn item and demanded a refund. They’re not rude. They’re exhausted and trying to get through their shift.

Someone left their shopping cart in the middle of the parking lot. You assume they’re lazy and inconsiderate. Reality: their kid is having a complete meltdown in the car. They’re trying to buckle a screaming toddler into a car seat while the toddler arches their back. They forgot about the cart. They’re not inconsiderate. They’re in survival mode.

We do this constantly. Assume malice when it’s usually chaos, confusion, overwhelm, or just not having the same context as the person targeted by malice. Incompetence and bad timing explain most problems. Malice is exhausting and rare.

The person who cut you off in traffic isn’t necessarily an asshole. Perhaps they didn’t see you. The friend who cancelled plans doesn’t think you’re unimportant. They’re dealing with something they haven’t told you about. The team member who didn’t deliver isn’t incompetent. They didn’t understand the requirement the same way you did.

Most of the time, people aren’t trying to make your life harder. They’re just trying to get through their own day with incomplete information and competing priorities.

Hanlon’s razor doesn’t mean you’re naive or you let people walk over you. It means you start with the more likely explanation before jumping to the least charitable one.

The most important take-away:

Check for misunderstanding before assuming malice. Ask questions before building a case.

“Hey, did you see my message?” is easier than silently resenting someone who didn’t even know you were waiting. “I noticed the dog barking at night” is more effective than deciding your neighbor is terrible. Most problems get solved faster when you assume ignorance instead of intent. Turns out a question works better than nursing a grudge about someone who forgot you exist.

Assuming good intent gets you halfway there. The other half is understanding that both sides usually have legitimate perspectives.

Third story

When two people disagree, each has their own story. Person A’s version. Person B’s version. Both feel completely right. Both are convinced the other is wrong. The conversation goes nowhere because you’re both defending their story instead of understanding the gap.

The third story is what a neutral observer would see. Not who’s right or wrong. Just the difference between the two perspectives, described without blame.

Your family member thinks you don’t care because you haven’t called in weeks. You think they’re being demanding because you’ve been drowning at work and they know that.

Their story: “You never reach out, I’m always the one calling, you don’t prioritize family.”

Your story: “I’m overwhelmed, they should understand, I’ll call when I have time.”

Third story: “We have different expectations about staying in touch, and neither of us communicated what we needed.”

Starting with your story: “You’re being unreasonable, I’ve been busy.” Defensive. Blaming. Going nowhere. Starting with third story: “I think we see this differently. You feel like I’m not making time, I feel like I’m doing my best under pressure. Can we talk about what we both need here?” Not assigning fault. Just naming the gap.

Two teams are in conflict. Engineering says product keeps changing requirements and expects miracles. Product says engineering is inflexible and doesn’t understand business needs. Each team has their story.

Engineering: “They never plan ahead, they’re always scrambling, we can’t build anything solid because they change their mind every week.”

Product: “They say everything takes forever, they don’t care about users, they hide behind technical complexity.”

Third story: “Engineering needs more stability to build well. Product needs flexibility to respond to market. We haven’t figured out how to balance both.”

Meanwhile both teams are convinced the other is the problem. They’re both right. They’re also both wrong. Welcome to organizations.

The us-versus-them version: each side defends their story, attacks the other side, nothing changes. The third story version: “Here’s the tension we’re both feeling. Let’s solve for both needs instead of fighting about who’s wrong.”

The key is get rid of absolutes.

“You never listen.”

“You always do this.”

“Everyone agrees with me.”

“Nobody thinks that’s reasonable.”

Absolutes make people defensive. They’re also usually not true. When you catch yourself using never, always, everyone, nobody, pause. Reframe without the absolute. “I’ve felt unheard in our recent conversations” is different from “you never listen.” One invites discussion. The other invites argument.

Third story doesn’t mean both sides are equally right. Sometimes one person is clearly wrong. But if you start by deciding who’s wrong, you’ve ended the conversation before it begins. Start with the third story. Describe the gap. See if you can close it. If someone’s actually wrong, that’ll become clear. But you’ll get there through understanding, not through accusations.

The pattern: stop defending your story long enough to describe the gap between perspectives. “You see X, I see Y, let’s talk about why” beats “you’re wrong” every time.

Finding the gap between perspectives works when the conflict is clear. But most situations aren’t even that clean - truth exists on multiple sides.

Gray thinking

Most people think in binaries. You’re either with us or against us. Something’s either good or bad. Someone’s either right or wrong. Gray thinking rejects this. It says both things can be partially true, the answer is usually “it depends,” and the nuance is where the actual insight lives.

Two of your acquaintances separate. Your mutual friends immediately pick sides. Team A says he’s the problem. Team B says she’s impossible. Everyone wants you to declare allegiance. Gray thinking asks: what if they’re both partially right? What if he did something thoughtless and she overreacted and they both handled it poorly and there’s no villain here, just two people who couldn’t figure it out? It takes two to tango. But picking sides is easier than admitting relationships are complicated, so Team A and Team B will fight about it at the next dinner party. Most relationship failures aren’t one person’s fault. But binary thinking demands you pick a side, so nuance gets lost.

Someone at work is struggling. Misses deadlines, seems disengaged, quality is slipping. The binary interpretation: they’re lazy and unmotivated. Gray thinking looks deeper: no onboarding, no support, hostile coworker making their life miserable, unclear expectations, personal issue they haven’t shared. Lazy is the easy label. The reality is usually more complicated. People aren’t failing in a vacuum. There’s a system around them, and that system might be broken. Worth asking the person how you can help. Sometimes listening is the most helpful thing you can do.

People are neither only good nor only bad. Good people do bad things. Bad people occasionally do good things. Your friend who’s generous and thoughtful also ghosted someone who didn’t deserve it. Your difficult coworker who complains constantly also stayed late to help you fix that critical bug. We want people to be all one thing so we know how to feel about them. Reality doesn’t cooperate.

Gray thinking is uncomfortable. Binary thinking is clean. “This is good, that is bad, I’m right, they’re wrong.” Simple. Satisfying. Usually incomplete.

Gray thinking asks: “What’s true about both perspectives? Where’s the tradeoff? What am I missing when I force this into either/or?”

Most strategic debates are stuck in false binaries. “Should we prioritize new features or tech debt?” Gray thinking asks: “What if the real question is when to prioritize each, or how to get some of both? Which tech debt actually blocks features? Can we sequence this differently?”

When you’re stuck in “this OR that,” step back and look for “this AND that,” or “this in these conditions, that in those conditions.” The nuance is where the insight lives.

You know what else is very good at binary thinking? AI. AI delivers confident, definitive-sounding answers that encourage it. Don’t fall into this trap. Hell, use AI itself to avoid it. Make it map the spectrum, not pick sides. Demand it to steelman opposing views. Ask it to generate the third story. My favorite: ask it to argue with itself until the nuances emerge. Bring popcorn, enjoy the show, and learn from it.

Gray thinking doesn’t mean everything is relative or nothing matters. It means rejecting false binaries so you can see what’s actually happening.

Next: Catching yourself being wrong

The six models above help you think through decisions, see systems, and not assume everyone’s terrible. Active frameworks you apply when you need them.

But your brain still lies to you. Constantly. It tricks you with vivid memories, follows crowds without checking, rewrites history to protect your ego, and feeds you information that confirms what you already think.

These aren’t things you can think your way out of. They’re built-in bugs in human cognition. The only fix is catching them before they cost you.

That’s the next essay: How not to be an idiot - the mental models that help you recognize when your brain is lying to you.

Part of a series on mental models: how to be less wrong, not be an idiot, lead without breaking your team, and build things without losing your sanity.

If you think someone else could benefit from this, please share it. Sharing is caring.