The monkeys you didn’t know you were collecting

Some thoughts on ownership, learning, and good intentions

You’re walking down the hall. Or opening Slack. Or skimming a doc. Someone says something like:

“Hey, quick question…”

“Can you sanity-check this?”

“I might be overthinking, but…”

“Do you have a minute?”

Nothing dramatic.

No fire, and no escalation.

Just a small, harmless obstacle.

You already have a full plate, probably more than a full one.

You don’t stop to ask whether this is yours.

You just… help.

If you do the thing right away — reply, fix, clarify, unblock — it’s gone.

You move on, feeling helpful, competent, and vaguely virtuous.

No monkey. No problem.

The trouble starts when you take it and don’t have the time to do it now.

You’ll reply later.

You’ll circle back.

You’ll get to it after this meeting.

Without realizing it, somewhere between being asked and actually doing the thing, you’ve adopted a monkey.

Not a big one.

A small one.

The kind that doesn’t scream.

The kind that waits.

The kind that multiplies.

The monkey you didn’t notice taking

I was reminded of the monkey article last week during a conversation with one of my team members.

She wasn’t overwhelmed in the obvious way.

Something just felt… off.

She told me she’d been getting a steady stream of requests lately.

Small ones. Reasonable ones. The kind that come wrapped in urgency and good intentions.

They usually sounded like this:

“We don’t have time to do this right now.”

“Can you just take care of it?”

“It’ll be quick.”

The work didn’t belong to her and everyone involved knew it.

It belonged to peers, or adjacent teams, or to people who were overloaded and trying to keep things moving.

None of the requests were outrageous.

None of them were framed as permanent ownership.

But taken together, they had a shape.

“It feels like these things don’t really belong to me,” she said.

“But somehow they all landed with me.”

She wasn’t describing overload.

She was describing ownership drift.

That’s when “Who’s Got the Monkey?” came back to me.

I stumbled on the article years ago, and it’s been a hit everywhere I’ve worked since. I recommend it heartily, because it gives teams a shared language for something they feel but struggle to name.

William Oncken Jr. defined a monkey as the next move in a problem.

Before a conversation, the monkey sits on one person’s back.

After the conversation, it sits on someone else’s.

In the original framing, this was a management problem.

A team member brings an issue.

A manager says, “Let me handle it.”

The monkey jumps.

Suddenly, the manager owns the next move.

The team member waits.

And the work stalls in between.

It’s a clean metaphor.

And it explains a lot.

But it mostly describes the loud version of the problem.

What my team member was experiencing was quieter — and more socially acceptable.

The monkey didn’t jump because no one cared.

It jumped because everyone was busy.

Ownership doesn’t always transfer. Sometimes it just… drifts.

What made that conversation uncomfortable wasn’t that the work moved.

It was how it moved.

No one was confused about ownership. Everyone knew where the work belonged. But time pressure changed the question.

Not “Who owns this?”

But “Who can do this fastest?”

So the request gets framed carefully.

“Can you just take this?”

“We’re slammed.”

“It’ll only take a minute.”

Temporary. Reasonable. Polite.

And helpfulness does the rest of the work.

Because saying yes doesn’t just feel fast — it feels kind. It feels like being a good teammate. Like keeping things moving. Like not making someone else’s already-bad day worse.

Saying no, on the other hand, doesn’t just slow things down. It risks feeling unhelpful. Or rigid. Or like you’re pushing back when someone else is already stretched thin.

So you don’t make a decision. You make an accommodation.

The monkey moves — not with a jump, but with a nod.

This is ownership drift.

Not a formal handoff. Not a deliberate choice. Just a series of small, well-intentioned yeses that quietly reassign responsibility.

And once that happens, two things change.

First, the original owner stops thinking about the problem. Not maliciously, just practically. As far as they’re concerned, it’s handled.

Second, the new owner inherits not just the task, but the next move. And the one after that. And the follow-up no one explicitly asked for.

What started as “can you just…” becomes background responsibility.

That’s how small acts of help turn into standing obligations.

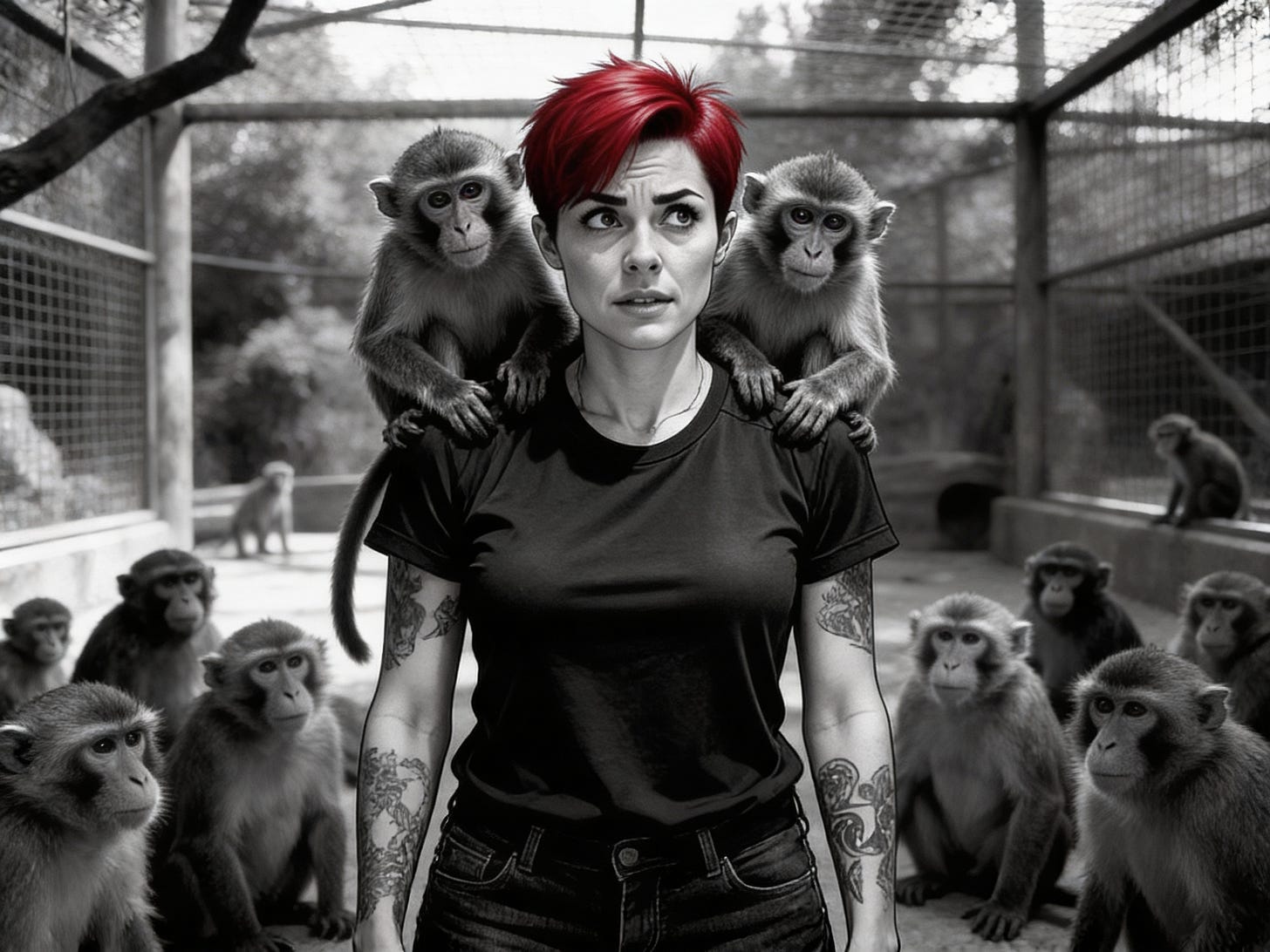

How monkey zoos are built (quietly, by the best people)

No one sets out to build a monkey zoo.

They’re not built by people avoiding work, or dodging responsibility, or looking for excuses. They’re built by the opposite.

Monkey zoos are built by people who respond quickly.

By people who notice gaps.

By people who step in when something is unclear or slowing down.

They’re built by the ones others trust.

Work has a natural tendency to flow toward competence. Toward the person who understands the context, knows the system, or can “just handle it.” And unless something actively resists that flow, it keeps going.

So small things start landing in the same place.

A quick follow-up.

A minor fix.

A clarification that “shouldn’t take long.”

Each one makes sense on its own. Each one feels helpful. Each one reinforces the same pattern: this is someone who can be relied on. you don’t collect monkeys though bad behavior, but through repeated proof of capability.

Over time, that reliability turns into gravity.

Congratulations.

The zoo is open.

The problem isn’t the giver

At this point, it’s tempting to look for someone to blame.

The team asking for help.

The peer who says, “We’re slammed.”

The adjacent group that keeps sending “small” requests.

But that’s not the problem.

In most cases, the people handing off work aren’t trying to offload responsibility. They’re trying to survive their own constraints. They’re making a local optimization under time pressure, with the information they have.

Instead of thinking, “How do I get rid of this?”

they’re thinking, “How do we keep this moving?”

And the person on the receiving end isn’t naïve. They often know the work doesn’t really belong to them. But they also know that pushing back takes time, negotiation, and social capital — all of which feel heavier than just doing the thing.

So the exchange happens.

The system quietly rewards relief over clarity.

That’s what makes this pattern so persistent. Everyone involved is acting reasonably. The outcome is what’s unreasonable.

What we actually trade away: learning

The real cost of ownership drift isn’t time.

Time is easy to see. It shows up in calendars, backlogs, and the feeling of always being a little behind.

The real cost is learning — and learning disappears quietly.

When you take a monkey and move things along, the work still gets done. Sometimes it gets done faster. Sometimes it even gets done better.

From the outside, everything looks fine.

But something subtle changes underneath.

The person who could have learned no longer has to sit with the problem. They don’t have to explore options, make tradeoffs, or live with the consequences of a decision — because the system offered a graceful exit.

And the person who helped doesn’t just do the task. They absorb the context, the follow-ups, the edge cases, and the unspoken expectation that they’ll probably handle the next one too.

Nothing breaks. No alarms go off.

But over time, patterns form.

The same people become the safe pair of hands.

The same people get asked “just one more thing.”

The same people stop learning — not because they’ve mastered everything, but because they’ve become the default.

Meanwhile, the people who could have grown don’t feel blocked. They feel supported.

That’s the uncomfortable part.

Learning didn’t fail loudly.

It was politely escorted out of the room.

Zoos don’t fill up because people stop learning.

They fill up because learning keeps getting deferred.

Sometimes you should take the monkey

None of this means you should never take the monkey.

Sometimes, taking it is the right call.

When time is genuinely critical.

When the risk is asymmetric.

When the cost of learning in the moment is higher than the cost of delay.

When someone is truly stuck and out of options.

When the problem actually is yours to solve.

In those moments, clarity matters more than purity.

For example:

A production issue is unfolding, and there’s no time for someone else to learn the system while customers are affected.

A cross-team dependency is blocking a release, and you’re the only one who can unblock it quickly because you have the context or the relationships.

You take the monkey.

You do the work.

You move things forward.

That’s not a failure of ownership, it’s judgment — and intention.

If you take the monkey, be honest about what learning you’re trading away and why.

The problem isn’t taking the monkey.

It’s taking it without realizing you’ve done so — or taking it out of habit, politeness, or reflex.

There’s a meaningful difference between:

“I’m taking this because it’s the fastest, safest option right now.”

and

“I guess I’ll just handle it.”

One is a conscious tradeoff.

The other is how zoos grow.

The goal isn’t to stop helping.

It’s to stop accidentally reassigning responsibility.

Awareness is a two-person job

This pattern doesn’t change by asking people to be tougher.

It changes by making the moment visible — on both sides.

Because ownership drift isn’t something one person does to another. It’s something that happens when two reasonable people make small, well-intentioned choices at the same time.

On one side, someone is under pressure. They’re trying to keep things moving, reduce risk, or buy themselves a little breathing room. Asking for help feels like the responsible thing to do.

On the other side, someone sees an obstacle and knows they can remove it. Helping feels kind. Efficient. Almost reflexive.

Neither person experiences the moment as a transfer of ownership.

One experiences relief.

The other experiences usefulness.

That’s why awareness has to be shared.

If only the “taker” is vigilant, they start feeling rigid.

If only the “giver” is careful, they start feeling unsupported.

The system only changes when both people can pause long enough to ask the same quiet question:

What’s actually being handed over here?

Not to block the work.

Not to score a point.

Just to notice.

Big monkeys, small monkeys — same system

The classic monkey story usually shows up in a very specific place.

A team member brings a problem.

A manager takes it.

The manager becomes the bottleneck.

Those are the big monkeys.

They’re visible.

They come with meetings and decisions and escalations.

They’re easy to point at after the fact.

But the same system is at work with much smaller ones.

The quick Slack reply.

The “I’ll just fix it.”

The follow-up no one explicitly asked for.

The context you carry so others don’t have to.

Those are small monkeys.

They don’t trigger alarms.

They don’t feel like ownership.

They rarely get named.

But they follow the same rule.

Whenever the next move shifts, whether through a formal decision or a quiet act of help, ownership moves with it.

The difference isn’t what moves. It’s whether anyone notices.

Big monkeys make the cost obvious, but small monkeys make it invisible.

If you only pay attention to the big ones, the system keeps leaking through the small ones.

One of the forces that makes ownership drift so persistent is something more human than urgency or process: helpfulness. Wanting to be useful, supportive, and easy to work with is often what makes these small handoffs feel reasonable in the moment. I explored that dynamic more deeply in another essay — not as a failure of discipline, but as an identity and incentive trap many capable people fall into.

A short field guide for returning monkeys (without being weird about it)

None of this works without language. Not policies or process, just language.

Most monkey transfers happen in passing: in Slack, in the hallway, in the last five minutes of a call.

If you’re about to take a monkey

Pause long enough to ask yourself one question:

Am I about to help, or am I about to own?

If it’s not truly yours, try one of these:

“I’m happy to help think this through, but I don’t want to take it over.”

“I can give you input — what are you leaning toward?”

“I can unblock you, but you should still own the next step.”

Translation: I’m here. The monkey stays with you.

Same support. Different outcome.

If you’re about to give a monkey

Be explicit about what you’re asking for.

“I’m stuck on this, but I still own it. Can you sanity-check my approach?”

“Can you help me think through the options before I move forward?”

“I don’t need you to do this — I need a second brain.”

Translation: I want help, not relief.

That one sentence preserves ownership without slowing things down.

If a monkey already jumped (and you want to give it back)

It happens. This isn’t about perfection.

When you notice it, rewind gently.

“I realized I picked this up too quickly. Can you take it from here?”

“I think I short-circuited your learning — want to run with it?”

“Let’s reset. What do you think the next move should be?”

Just clarity. Be direct, no drama, no apology tour required.

If it’s actually okay to take the monkey

Name it.

“This one’s time-critical. I’m taking it.”

“The risk is high here — I’ll handle this part.”

“I’ll own this now, and we’ll walk through it afterward.”

Naming the exception keeps it from quietly becoming the pattern.

The smallest, most powerful question

Over time, I stopped trying to guess what people were really asking for.

Now, when a team member comes to me with a problem, we talk it through. We look at the options. We unpack what’s actually blocking them.

And then I ask a very simple question:

“Do you want to do this yourself, or do you want me to handle it?”

Ninety-nine percent of the time, the answer is:

“No, I want to do it.”

They always did.

What they wanted wasn’t relief.

It was reassurance.

Or a second brain.

Or permission to trust their own thinking.

That question doesn’t slow things down. It speeds the right things up.

Now everyone knows where the monkey is, who owns the next move, and what learning we’re choosing to keep.

That’s the real shift: not being less helpful, but being more intentional.

Not hoarding monkeys. Not refusing them either.

Just noticing — together — when one is about to jump.

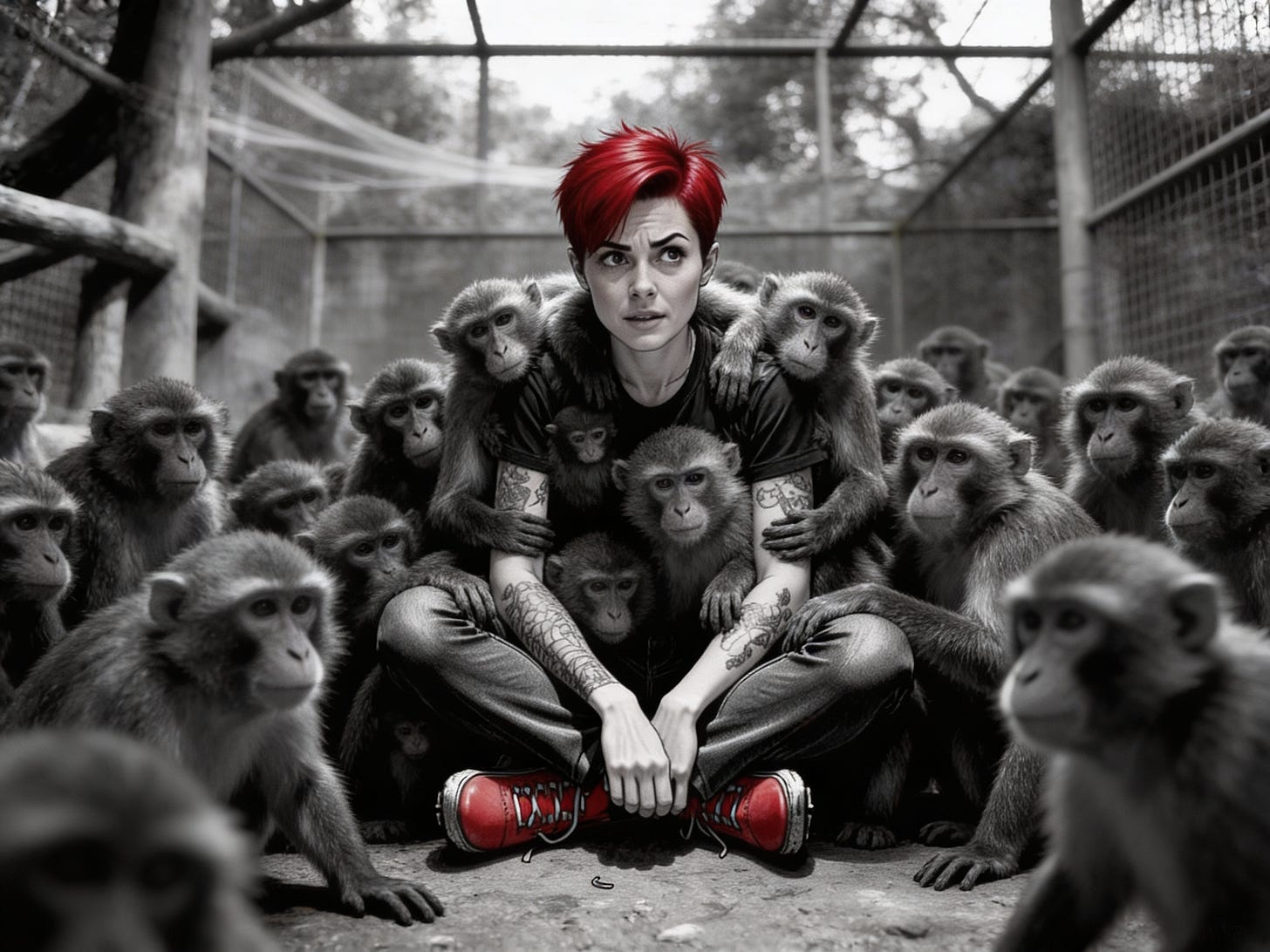

Zoos aren’t built by bad leaders or by bad people.

They’re built by good ones who never stopped to ask:

“Whose monkey is this—really?”

This piece lands because it names something almost everyone feels but rarely has language for. It’s not about laziness, boundaries, or bad teammates. It’s about how responsibility migrates when awareness drops.

From a CTM perspective — Cognitive Transformational Mindfulness, the mindfulness framework I developed and share on Substack — what you’re describing is a classic case of unconscious coherence-seeking. The system isn’t failing; it’s trying to stay smooth.

CTM starts with a simple observation: when awareness is fragmented, systems default to the fastest path to relief. In this case, relief looks like competence absorbing friction. The “monkey” moves not because anyone chose ownership, but because the group’s nervous system preferred continuity over clarity.

That’s why this isn’t solved by better policies or firmer personalities. It’s solved by restoring reflective space in the moment of transfer.

What CTM adds is the internal layer beneath the behavior:

Helpfulness feels good because it restores short-term coherence.

Saying no feels bad because it introduces momentary dissonance.

Without reflection, the body chooses coherence now over sustainability later.

This is why monkey zoos are built by the most capable people. Their systems regulate others before checking whether they’re regulating themselves.

Your strongest insight is this one: the real cost isn’t time — it’s learning. In CTM terms, learning requires tolerating mild incoherence long enough for integration to happen. When someone “rescues” a task too quickly, the system resolves tension before meaning can form. The work gets done, but awareness doesn’t grow.

Brilliant, this is so real, but seriously, what are your best tecniques for keeping these little monkeys from taking over, cause your insight here is just amazing.