Debating physics in a room full of poets

Why engineering leadership often feels like reasoning in an unreasonable system

The universe served me this quote today, and it landed with perfect timing, as if it knew I had a story and a lesson to share.

“Of course it is exhausting, having to reason all the time in a universe which wasn’t meant to be reasonable.”

Kurt Vonnegut

At least every person with an engineering mindset I know has lived some version of this line.

I’m sure every engineering leader has felt it more than once, especially when trying to translate technical complexity or risks for people who reason differently.

Those moments are not about “us versus them,” but about noticing where our own mindset might be limiting what we can learn.

The tension is real

Inside the head of someone with an engineering mindset, the world is supposed to make sense. We are either trained, or simply wired, to look for logic, consistency, and clear cause and effect.

Our default assumption is that problems can be understood if you break them down, reason about them, and follow the data. We usually thrive in systems where reasoning matters and ambiguity can be contained.

But in my experience organizations rarely work that way.

They move through intuition, shifting priorities, urgency, and the lively, sometimes irrational energy of human decision making. People reason in narratives, instincts, constraints, and trade-offs that are not always visible on the surface.

From the inside, this can feel like two operating systems trying to run the same application.

Both valid. Both necessary. But built very differently.

When these two systems meet — the logic-driven mind and the reality of human decision making — they collide often, and when they do, the gap between them can be exhausting.

When logic meets “common sense”

Here is the moment many people with an engineering mindset recognize instantly.

You walk into a meeting with your data, your scenarios, your risk assessments, and your carefully reasoned trade-offs. You have a model in your head, a map of how the decision should unfold if everyone is using the same logic.

And then you run straight into:

a strong gut instinct

flexible and subjective “common sense”

assumptions liberally used as facts

business pressures that do not match your reasoning model

Inside your head, you are thinking, “Wait… what? How does that follow?”

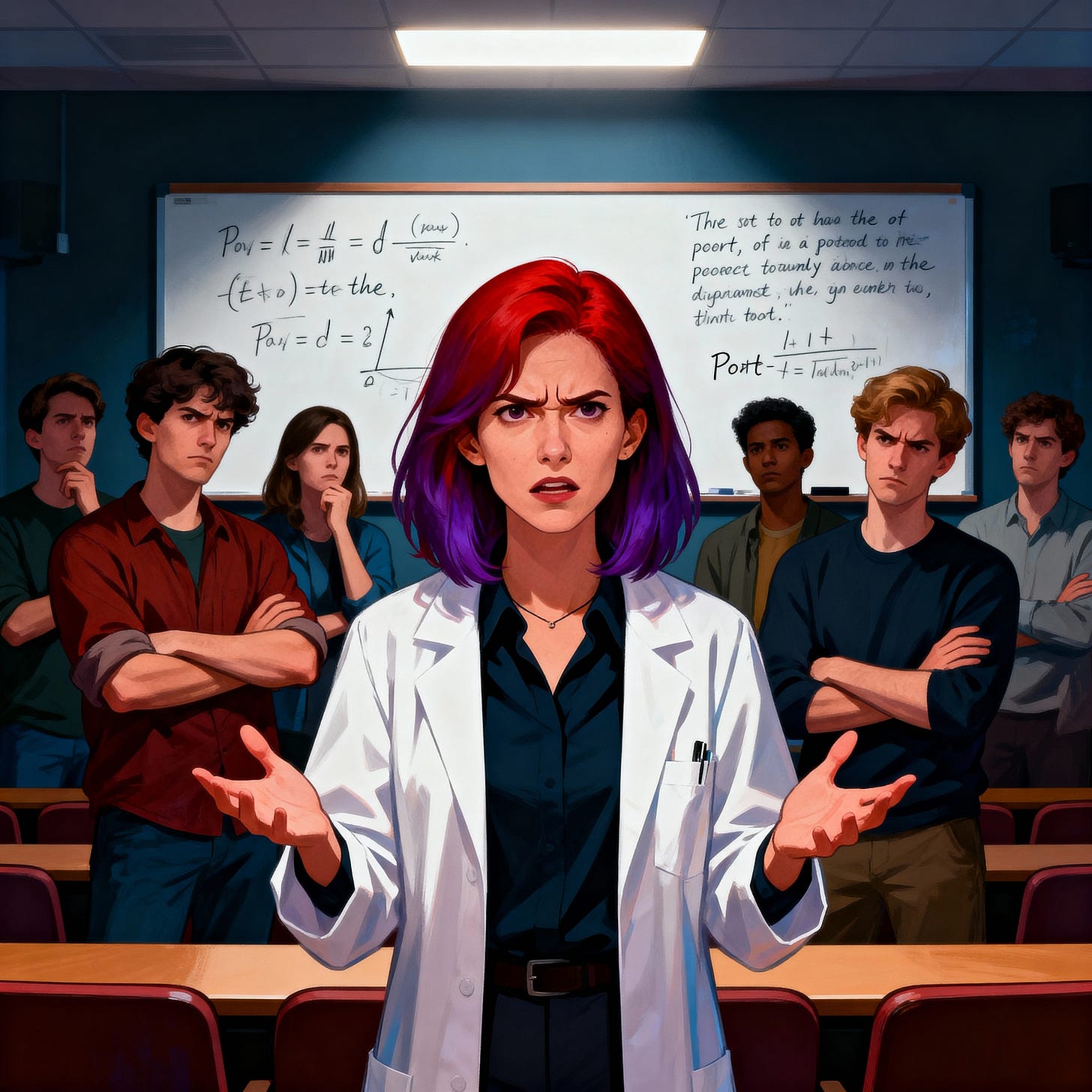

After a few rounds of this, it starts to feel like debating physics in a room full of poets.

At first, you reason.

Then you push.

Then you start to butt heads.

You hit wall after wall with logic-based arguments.

You watch people reshape “common sense” to fit their preferred reality.

And meeting after meeting like this, your inner monologue shifts from “Let me explain again” to “Why is this so hard?” and eventually to the most dangerous one of all: “I don’t care anymore.”

This is one of the worst outcomes for any smart and thoughtful person who genuinely wants to build something meaningful.

Stop before you get there.

Because once you reach the point where you stop caring, the problem is no longer the meeting, the project, or the stakeholders. It becomes something much more personal: your sense of ownership, your motivation, and your connection to the work itself.

The turning point is not pushing harder with logic. It is recognizing that logic alone cannot carry you through environments built on human complexity.

When logic alone doesn’t make it

I have been in that place many times.

And it took me a while to understand that the answer was not more logic, more reasoning, or more data. Those tools matter, but they are only part of the equation.

To navigate environments shaped by humans, you need a different operating model. One that relies less on proving you are right and more on understanding the system you are working inside.

For me, that shift came from these four principles:

assuming good intentions, so I start from trust instead of defensiveness

genuine curiosity, so I explore what I might be missing instead of focusing only on what I know

humbleness and open-mindedness, so I can put my logical ego aside long enough to hear perspectives that do not match my own

determination, so I stay focused on solving the problem or preventing it, not on winning the argument

This was not about becoming softer. It was about becoming more effective.

And no, I did not suddenly start reading poetry, to be clear. Neither did I start learning new languages.

But I did begin approaching conversations with the patience of someone who recognizes that people are not malfunctioning machines. They simply operate with different inputs, experiences, pressures, and incentives.

This mindset shift changed a lot for me.

It lowered my frustration, improved collaboration, and made me far more effective across teams.

It also helped me realize something important: logic is not weakened by curiosity or humility. It becomes stronger, because it is grounded in a fuller picture of reality.

Does it work every time? Of course not. But it works far more often than butting heads or speaking louder. And do I use it every time? No, but I try.

I 100% use it when I have slept enough, when my patience buffer is full, and when I am genuinely ready to approach the conversation with clarity instead of ego.

On the days when I cannot do that, I try to recognize it early and give myself some grace. No one shows up as their best self all the time, and forcing it usually backfires. What matters is noticing the pattern.

Frustration, tension, or that familiar tightness behind the eyes usually means something important is happening beneath the surface. It’s not a sign that the other person is wrong or unreasonable. It is a sign that something in my approach, expectations, or understanding needs attention.

And once I actually paid attention to that signal, it paid me back with fewer battles and better conversations.

Frustration is a signal, not a dead end

For a long time, I treated frustration as proof that something was broken.

The system.

The process.

The communication.

The other person’s logic.

But eventually I realized something important: frustration is rarely about the other person.

It is usually about the gap between how we expect a situation to behave and how it actually behaves. Frustration is information. It tells you something in your approach, expectations, or understanding needs attention.

Once I started paying attention to that signal instead of pushing through it, I learned a few things:

frustration often means I am trying to solve a human problem with a too logical solution

frustration usually appears when I am clinging to my perspective and ignoring the unseen constraints of others

frustration is a clue that the problem is more complex than my current model accounts for

In other words, frustration is not a wall. It is a signpost.

And if you follow it with curiosity instead of annoyance, you usually discover something valuable: missing context, misunderstood constraints, unspoken fears, or priorities that were never surfaced.

This shift in how I respond to frustration changed the way I lead.

Instead of escalating the tension, I started slowing down and asking better questions.

Instead of pushing harder with logic, I started exploring what I did not yet understand.

Frustration still shows up. I am human, after all, remember? But now, when it does, I treat it as an early indicator that my model needs adjusting.

And that brings me to the practical side of all this: what helps when you are reasoning in a system that is not always reasonable? But before I touch this, there’s something that needs to be said first.

There’s the other side of the moon, too

Not every moment of frustration is a signal about you. Sometimes it is a signal about the other person.

There are situations where you drill deeper, ask questions, explore context, and really try to understand what is happening. You stay patient, curious, open-minded… and nothing shifts.

Because sometimes people are simply being unreasonable. Or they are unwilling to reflect. Or they refuse to meet you even halfway with their own thinking and self-awareness. It happens more often than we like to admit.

Curiosity, empathy, and patience are powerful tools, but they are not unlimited, and they should definitely not be one-sided. They only work when there is at least some willingness on the other side to participate in the reasoning process.

When that willingness is missing, you are allowed to be human, too.

You are allowed to feel frustrated.

You are allowed to set boundaries.

You are allowed to have the difficult conversation the situation requires.

This is not giving up.

It is recognizing that leadership is not about carrying the entire emotional and cognitive load yourself. You can invite someone into a better conversation, but you cannot drag them there.

And when someone refuses to step in with you, that is information as well.

Sometimes the most reasonable response is clarity, not more patience. Putting it together is quite simple, but important:

Navigating an unreasonable system does not require perfection, heroic patience, or unlimited emotional bandwidth. It requires a practical toolkit that helps you show up with clarity, adapt when needed, and protect your energy when things get messy.

So… what helps (most of the time)

Here is what made a difference for me. None of it is magic, and none of it works every time, but these habits consistently move things in the right direction.

Expect humans, not machines

This is not a negative view of people. It is a realistic one.

Decisions are made by people, and decision making blends logic, pressure, incentives, timing, and emotion.

It also reflects something we all know but often forget: humans are not purely rational beings. Emotions, values, beliefs, habits, and biases shape us. We are, frankly, down irrational at times. Every one of us. Including you and me.

Recognizing this is not lowering the bar for reasoning. It is understanding the system you operate in. When you calibrate your expectations to how people actually think — not how ideal models assume they should think — your influence grows, your communication sharpens, and your frustration level drops.

Speak their language

Drop the jargon. Ask about users, revenue, runway, use cases, and pain points, their view.

Clarify what they mean, and what you mean, even if you think you are using the same words. Many disagreements come from assuming shared definitions that simply are not shared. I kid you not.

Connect your reasoning to what the other person is responsible for or worried about. When you do that, the conversation usually shifts from “who is right” to “what will work.”

And yes, sometimes you even change your own mind. Mindblowing, I know. But it happens.

Pick your battles

Push hard on irreversible decisions or ones that set long-term direction.

For everything else, take a thoughtful leap of faith. Jump if you must, but bring your parachute. Metrics, logs, rollback paths, and mitigation plans are the parachute. You cannot defy gravity with willpower alone, but you can reduce the impact of the fall.

Let outcomes do the talking

Track what happens. Share what you observe. Look at patterns, not anecdotes.

If things improve, keep going. If they do not, adjust.

And if nothing changes after several cycles, reconsider your approach. And yes, sometimes that also means reconsidering your options. All of them — including your environment.

Help your team reason in an unreasonable world

Once you start navigating complexity with more clarity and less frustration, something else becomes obvious: your team needs this skill set too.

It is not enough for a single person to understand how to reason inside an unreasonable system. Teams need shared language, shared mental models, and shared expectations. Otherwise, the frustration simply moves around the room instead of being reduced.

Coaching and mentoring matter. Help your team see the difference between logic failing and context missing. Show them how to ask better questions, not louder ones.

Model the patience you expect from them, even if you are still learning it yourself.

Teach them how to translate their reasoning into the language of the people they work with. And when needed, step in to prevent an “us versus them” mentality from taking root.

Teams do not become cynical overnight. It usually happens in small moments of misunderstanding, misalignment, or disappointment. Cynicism is the silent poison.

When you coach your team through those moments, you bring back a bit of sanity and show them how to stay effective without losing their energy or optimism.

And the more teams learn how to reason together across different thinking styles, the less daunting the unreasonable world feels.

The real beginning of leadership

Reasoning in a messy system is exhausting. But it is also the place where real leadership begins.

Leadership is not about having the perfect logical argument. It is not about being the smartest person in the room. And it certainly is not about grinding through every disagreement with sheer will.

Leadership begins when you learn to bridge logic with humanity. It starts when you recognize that people are not problems to solve, but systems to understand.

It begins when you can stay grounded in your own reasoning while still being open to the reasoning of others.

To me, real leadership looks like:

bringing clarity into ambiguity

staying curious when things do not make sense

choosing influence over insistence

protecting your energy without withdrawing your care

helping others reason better, not just pushing your own logic harder

This is the quiet, often invisible work that turns people with the engineering mindset into leaders and turns leaders into trusted partners.

Most of it happens in the hard moments: the confusing meetings, the mixed signals, the pressure, the friction between how things should work and how they actually work. Those moments are not obstacles to leadership. They are the training ground.

If you are willing to treat them that way, the unreasonable system becomes a little more navigable, a little more human, and a little less exhausting.

That’s where the real growth happens.

Food for thought… to go

Take this last thought as your “coffee to go” for your mind:

Leadership tends to begin exactly where your comfort ends.

If you look at your next difficult conversation through this lens, what might you learn about yourself, your team, or the system around you?

And here is a question worth pondering upon:

Do you consider yourself a reasonable person?

Most of us do. No surprise here.

But the more interesting question is whether the people you work with would agree.

If you are feeling brave, ask a few of them. Their answers might surprise you. And they might show you something important about how you lead.